"The hierarchy of warmth": China's three-track subsidy system

In Shandong Province, heating subsidies pay officials $590 and the poor just $86.

One of the most heated topics trending on the Chinese internet is the plight of Hebei's freezing villages: Rural households around Beijing say they can no longer afford gas or electricity for heating after subsidies shrink.

As the second installment of our China 101 series, this piece tries to map China's subsidy ecosystem: a labyrinthine, fragmented, stratified yet surprisingly transparent regime.

Put it simply, in the same winter, three vastly different systems are running simultaneously.

As noted in our previous guide on official rankings, privileges in China’s vast civil service, from income to social status, are inextricably tied to hierarchy. It should be no surprise, then, that the subsidy system follows the same logic.

Today's piece starts with Shandong's heating subsidies and uses them to map China's three-track system:

The state-apparatus track: a largely self-contained “official” system.

The social-insurance track: funded mainly by employers and the state, covering only urban employees and a relatively narrow population.

The social-assistance track: a basic safety net for the poorest, with benefit levels that have long remained low.

The numbers tell a more vivid story. In Shandong, a retired bureau-level official can receive 4,100 yuan a year (about $590). In contrast, rural recipients of subsistence allowances and extreme-poverty aid receive 600 yuan per household (about $86).

This article was first published on Nov 19, 2025, on the WeChat account 青年志Youthology, which describes itself as approaching youth culture through sociology and anthropology, while also offering business consulting.

Please note the following translation is my own and has not been reviewed by the authors.

山东采暖补贴,揭开了补贴体系的三套逻辑

Shandong's heating subsidies unveil the three logics behind China's subsidy system

At the Start of Winter this year, Shandong Province released its heating-subsidy standards, triggering a huge reaction online.

Enterprise retirees receive 1,700 yuan per person per year, while retired government employees are paid on a tiered scale by administrative rank, up to 4,100 yuan a year for Bureau-Director level (厅局级正职) officials. Urban recipients of subsistence allowances and extreme poverty aid receive 600 yuan per household; their rural counterparts receive 300 yuan per household. Orphans and children in severe hardship receive 300 yuan per person, and unemployed people receive 185 yuan per person.

Set side by side, these gaps are bound to be startling. And yet, on reflection, they are not entirely surprising. They are a reminder that the "dual-track system" and distributional distortions are not confined to wages and social security; they also run through a vast, rarely discussed subsidy system.

Most people know that subsidies exist for housing, healthcare, transportation, and more, but few know the details. Differences in how benefits are allocated, like the heating subsidy, often invite uneasy reflection.

This article aims to map just how large China's subsidy system is, and what kind of distributional structure lies beneath it.

1. China's Off-payroll Subsidy System

To understand the distributional logic behind heating subsidies, it helps to start with China's vast subsidy system. It may look complicated, but if you trace it through the government's budget classification, it is not hard to decipher — and can be surprisingly transparent.

In fiscal spending, most subsidies are concentrated in a few line items: chiefly 30102, "Allowances and Subsidies," supplemented by smaller amounts under 22102, "Housing Reform Expenditure," and 303, "Assistance to Individuals and Families."

In statistical reporting, these are further grouped into five broad categories: Nationally Uniform Allowances and Subsidies — Standardized Allowances and Subsidies — Reform-Related Subsidies — Incentive (Reward) Subsidies — Other.

National Uniform Allowances and Subsidies are issued centrally by the State Council, or by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the Ministry of Finance. They are the most standardized part of the system, such as hardship allowances for remote areas and post allowances.

Standardized Allowances and Subsidies stem from the standardization overhaul in 2006. The reform aimed to "package and merge" the diverse allowances and bonuses previously set up by departments and localities themselves, eventually settling them into two large baskets: work-related allowances and living subsidies. In essence, it was an attempt to end the chaotic, fragmented landscape of agency-based benefits.

Reform-based Subsidies follow another thread. As welfare provision was monetized, in-kind benefits once provided by work units — housing, vehicles, medical care — were gradually converted into cash subsidies, such as housing monetization subsidies and transportation subsidies introduced through official-vehicle reform. But these subsidies have a clear historical cutoff: they largely apply to personnel who were "on-staff and on-post" (在编在岗) at the time of reform, and they are not indefinitely open to new entrants.

Reward-based Subsidies and other subsidies form a more flexible block, essentially another type of incentive outside of wages. After the introduction of the central authorities' Eight-Point Decision (八项规定), this portion was significantly tightened: local "hidden welfare bonuses" and "performance bonuses" were either cleared out or folded into performance-based wages.

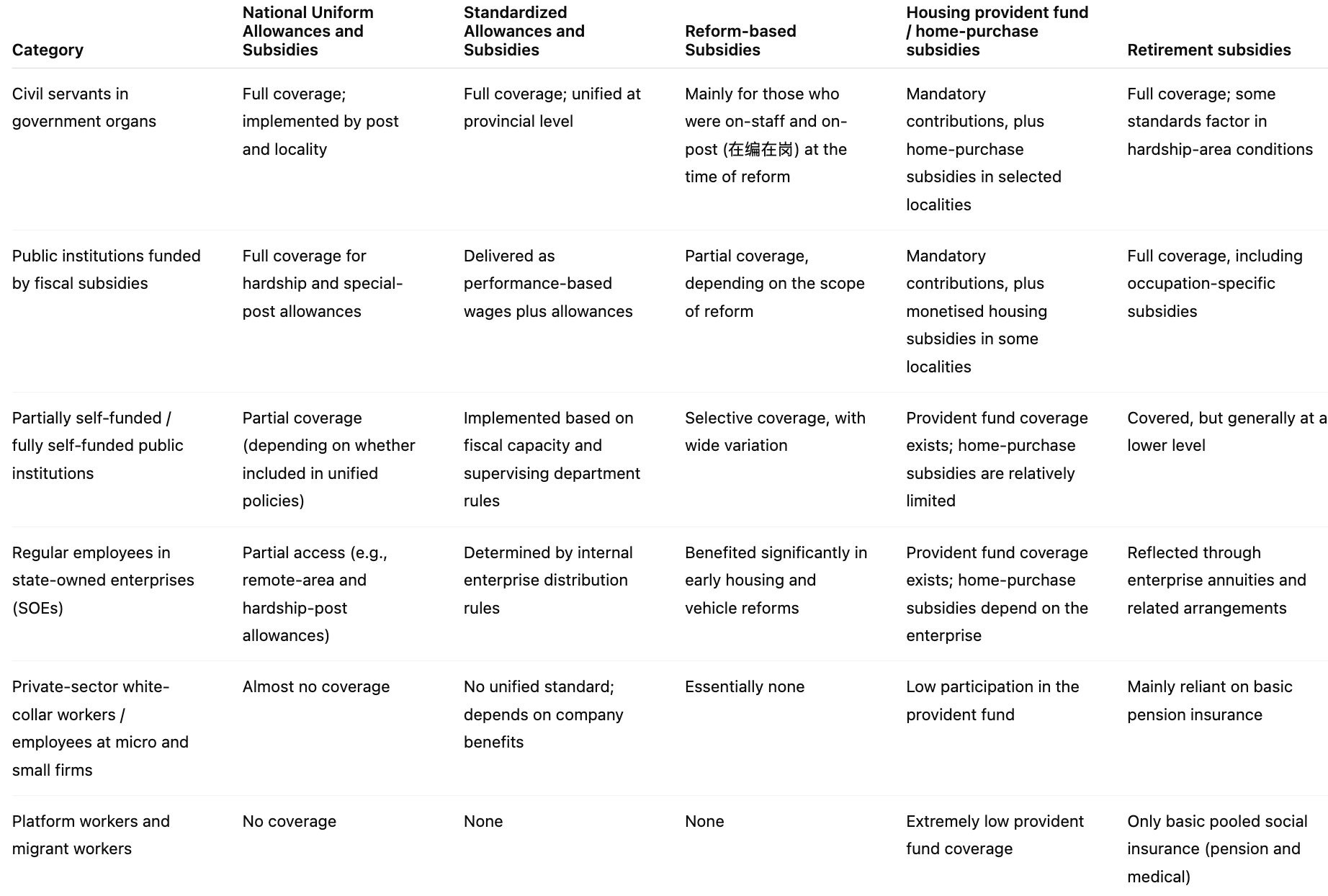

Seen this way, the subsidy system is not a random pile-up. It unfolds along a recognizable sequence, uniform → standardized → reform-related → incentive-based, and is embedded in formal fiscal categories. The table below may help clarify the key question this structure raises: who gets subsidies, and how are benefits stratified across different groups?

2. Where Do Different Subsidy Standards Come From?

Back to Shandong's heating subsidies: why are the gaps between social groups so large? The reason is that there is no single unified standard. Instead, the subsidies come from three separate systems: Income Welfare, Social Security, and Social Assistance.

Cadres and civil servants fall under "Income Welfare." As early as 2006, Shandong issued a document jointly by the provincial Department of Finance and the Department of Construction, linking heating subsidies to administrative rank: the higher the rank, the higher the subsidy. The document circulating online this time is essentially part of the civil-service system's broader income-benefit package.

Retired enterprise employees are on a different track. Their heating costs are covered through a "Special Fund for Heating Subsidies," funded jointly by employers and local government.

In practice, the subsidy are usually not linked to rank or position. Instead, they are paid as a flat per-capita amount, set with reference to local heat tariffs, the typical heated floor area of ordinary housing, and what public finances can sustain. This falls under the umbrella of social security benefits and has never been integrated with the government system's rank-based hierarchy.

Meanwhile, groups such as rural subsistence allowances recipients, people in extreme hardship, and other vulnerable groups (including children in severe difficulty) fall under the "Social Assistance System."

They are neither part of the state apparatus nor fully covered by the urban-rural employee welfare framework. At this level, policy targets shift from the individual to the household. Under Shandong's social assistance rules, subsidies for urban and rural households are calculated based on floor area, unit price, and the length of the heating season, with urban standards roughly twice those in rural areas.

So, in the same winter, three systems operate in parallel:

The state-apparatus track: a largely self-contained "official" system.

The social-insurance track: funded mainly by employers and the state, covering only urban employees and a relatively narrow population.

The social-assistance track: a basic safety net for the poorest, with benefit levels that have long remained low.

In practice, the second track reaches only a minority, because many in China are not classified as "urban employees城镇职工" but as rural and non-working urban residents城乡居民, flexibly employed workers, or migrant workers — groups that often cannot access the full social-insurance welfare package.

The third track is social assistance aimed at the destitute, and its subsidy levels have remained low for years. The result is structural stratification: benefits within the government system continue largely unchanged, employee-based social insurance covers only a limited population, and the broadest groups are left outside a sustainable welfare framework.

This same three-track split extends well beyond heating subsidies — to high-temperature allowances, transport stipends, and housing subsidies, among others. That makes the most practical reform direction fairly clear: expand the coverage of the second track and gradually align the first track with it, while raising benefit levels under the third track. In reality, though, delivering on that agenda would be extremely difficult.

3. Flexibility, Standards, and a Safety Net That Falls Short

With the three tracks laid out, we can now look inside them — compare how they operate — and see the logic that drives the differences. The starkest contrast appears in the single largest area of spending: housing.

Start with Track II, the "urban employee" system, which is probably the one most people know best. It sets the contribution rates for the housing provident fund (HPF) paid by employers and employees: in general, each side should contribute no less than 5%, while the upper cap is set locally and usually does not exceed 12%. Within the same employer, the employer contribution rate should in principle be uniform across staff, and the employee contribution rate must not be lower than the employer's. These contributions can be used for home purchases, renovation, or rent, and constitute a standardized entitlement explicitly protected by law.

Now consider Track I: government agencies and affiliated public institutions. When it comes Here, the degree of discretion in housing benefits is striking. Take Tianjin as an example. A 2025 policy specifies that the supplementary housing provident fund contribution rate for "municipal-level agencies and public institutions managed under civil-service rules" can be as high as 30%. The contribution base can be adjusted to an employee's average monthly total wage bill, with a ceiling set at three times the average wage (around RMB 27,861). That rate is nearly six times the typical cap under the urban-employee system, and much of it is borne by the employer, underscoring how flexible, and how generously insulated, this track can be by design.

And that is only part of the picture. People within the state apparatus may also receive additional housing-related benefits, including:

Housing monetization allowance: After the state ended welfare housing distribution in 1998 , state apparatus personnel were issued a one-time differential subsidy based on rank and area. In Beijing , below section level is 60㎡ , section chief/deputy is 70㎡, deputy division head is 80㎡ , division head is 90㎡ , deputy bureau head is 105㎡ , and bureau head is 120㎡ .

Rent Subsidy: Employees who rent may receive subsidies keyed to administrative rank.

Home-purchase subsidy: In some localities, civil servants may be eligible for fiscal support for home purchases — for example, housing subsidies and discounted purchase schemes reported in Zhanjiang, Guangdong, in 2024.

Talent housing: Core staff on established posts in universities, research institutes, public hospitals, SOEs, and high-tech firms may also receive extra support such as talent apartments and settling-in allowances.

In short, compared with the rule-bound design of Track II, Track I is far more discretionary — and that discretion is a defining feature of many subsidies within state apparatus. By contrast, rural and non-working urban residents, flexibly employed workers (who can contribute to the housing provident fund only in some pilot cities), and those outside any formal welfare framework are largely excluded from housing subsidies. Government-subsidized housing exists, but it is often tied to household registration (hukou), making it hard to turn into a broadly accessible, universal form of support.

Seen this way, the direction of subsidy reform is not hard to identify: reduce the discretionary space in Track I, align it progressively with the standards of Track II, raise those standards, and extend coverage to a much wider share of the population.

4. A Vast Subsidy System That Is Hard to Roll Back

After mapping the subsidy system’s architecture, the next question is scale: how large is it in practice?

Take "personnel expenditure" within the general public budget as an example. In 2022, personnel spending accounted for roughly 27% of national general public budget expenditure, described in academic work as "high in share, fast-growing, and highly rigid". Within personnel spending, allowances and subsidies have long made up around half of wage-based income, pointing to an imbalanced pay structure. On a rough estimate, off-payroll fiscal payments (including various allowances and subsidies) amount to about 13% of general public budget expenditure — roughly 2%–3% of GDP — potentially reaching RMB 4 trillion.

The sheer scale has historical roots. Reform of the civil-service pay system has lagged, and base pay was not raised in step for a long time. Many localities therefore used allowances and subsidies to lift incomes indirectly, driving the base-pay share down to around 23%–30%, while allowances and subsidies rose to 60%–70%.

The nationwide 2006 campaign to "standardize civil-service allowances and subsidies" focused on cleaning up locally created items and unifying standards and funding sources — its core aim was regulation and standardization, rather than deep cuts.

A 2019 State Council notice on reforming the civil-service pay system pushed further: it called for higher rates for position pay and grade pay, folding some standardized allowances, subsidies, and performance pay into base pay, and "appropriately increasing the share of base pay", while freezing or tightening the growth of allowances and subsidies. In large cities, this brought the split between base pay and allowances closer to 1:1, but in some smaller cities the gap remains pronounced.

After 2023, the "tighten our belts" principle has led many localities, under growing fiscal pressure, to adjust performance pay and allowances and subsidies. In a sense, this has been the first real test of the allowance-and-subsidy system.

Why is it so difficult to scale these subsidies back? The challenge lies not only in institutional design, but also in the way fiscal constraints, administrative rules, and incentive structures have become tightly intertwined.

First, at the level of institutional design, the core aim of the pay reforms in 2006 and again in 2015 was not to slash allowances and subsidies across the board. It was to standardize them by consolidating the previously fragmented, catch-all items into a small number of authorized categories, and folding part of these payments into base pay. In practice, however, this is difficult to implement.

The decisive constraint is the structural tension built into the fiscal system. The central government sets the nationally unified baseline for base pay, but local governments retain the real discretion over the allocation of allowances and subsidies — and most of the funding burden also sits with local budgets. This turns allowances and subsidies into a de facto adjustment valve for local "personnel authority" and "fiscal capacity": a tool to manage staffing pressures and budget realities at the same time.

Under soft budget constraints, it becomes the most malleable part of the entire system. If the central government were to compress allowances by fiat, it would either cause a sharp fall in officials’ take-home income — creating political risk — or force the central budget to assume the full cost of these payments, which is close to impossible under today's fiscal pressures.

Moreover, after the anti-corruption campaign and the crackdown on "three public expenses" (official hospitality, government vehicles, and overseas official travel), allowances and subsidies to some extent became a form of sanctioned compensation. Against that backdrop, large cuts could weaken the day-to-day functioning of local governments and agencies. In practice, many localities try to prevent a steep fall in take-home pay in order to preserve basic incentives.

That is why, even when fiscal stress intensifies, rolling back allowances and subsidies remains a complex and slow-moving process.

Against this backdrop, the controversy over Shandong's heating subsidies is not an isolated incident but a microcosm of China's highly fragmented subsidy regime. As noted above, a long-standing three-track stratification — government agencies, urban employees, and social assistance — has produced clear tiers and, with them, unequal treatment across groups.

The policy direction is clear: curb the exceptionalism and discretion built into the government-agency track, and expand both the coverage and standards of the urban-employee track. Yet rolling back entrenched benefits and pushing reform through is extraordinarily difficult. Still, a regime long seen as "too rigid to retrench" is, for the first time, facing a genuine test. When local finances can no longer sustain this supposedly flexible adjustment valve, a window for change may finally be opening.

Looking ahead, will a subsidy regime rooted in the divide between those inside and outside state apparatus be forced, under fiscal stress, toward integration, or will it become even more ad hoc as governments seek cheaper ways to plug local budget gaps? The answer will be a test of distributive fairness, and of what comes next for China's social settlement. Enditem