A practical guide to identify a Chinese official's rank

Prof. Nie huihua's elaboration on the political logic of Chinese official ranks

To make sense of China’s policy decisions, it is necessary to understand the people who make them.

China’s bureaucracy has gone through many rounds of reform, but promotion and rank remain at its core. Much like in traditional China, hierarchy still structures the careers and daily realities of today’s officials.

For the country’s vast civil service, political privileges, income, social status and organizational authority are all closely tied to rank. As the main actors in public governance, civil servants’ incentives and behavior directly shape how the state is governed. Promotion, in other words, is not just a personnel issue, but also underpins the logic of governance itself.

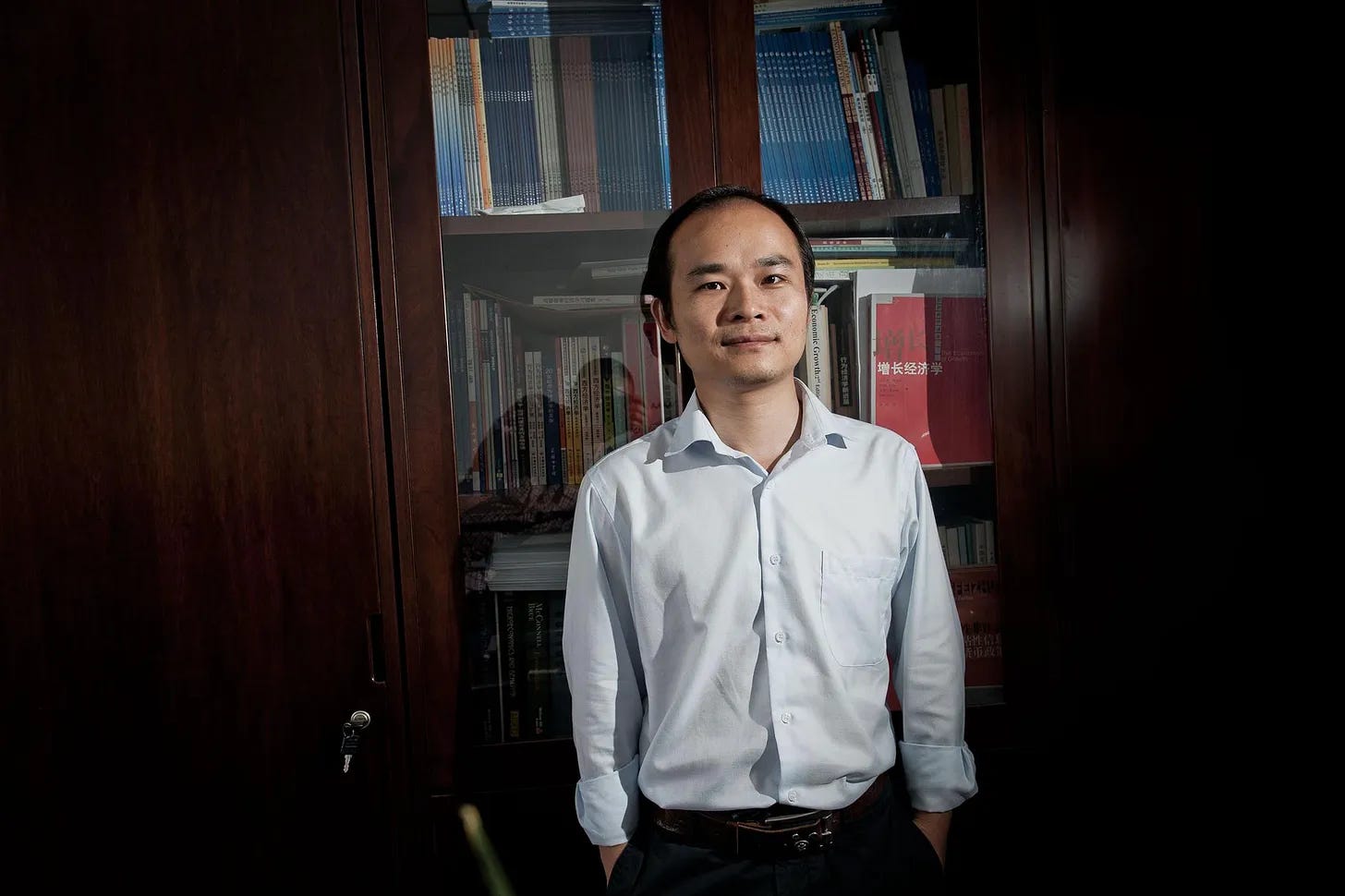

Today’s newsletter looks at this logic through an essay, “The Political Logic of Chinese Official Ranks 中国官员级别的政治逻辑,” by Prof. Nie Huihua (聂辉华) and Dr. Gu Yan (顾严), first published in 2015 on FT Chinese.

Prof. Nie, a professor at Renmin University of China, has spent many years studying China’s primary-level government. He earned his degrees in China and completed a year of postdoctoral research at Harvard University under Nobel laureate Oliver Hart.

Dr. Gu, when the article was published in 2015, was an associate research fellow at the Social Development Research Institute of the National Development and Reform Commission. He now serves as Director of the First Research Division at the Research Center for Xi Jinping Economic Thought.

The essay is also included in Prof. Nie’s recent book, The Governance Logic of Primary-Level China, an excerpt of which I shared earlier and many readers said they enjoyed.

In this piece, the authors lay out, in a systematic and accessible way, how to identify the ranks of Chinese officials, including a number of special cases. It works as a practical guide to surveying the complexity and internal discipline of China’s officialdom from above.

Below is my English translation of the piece, shared with kind permission from Prof. Nie.

中国官员级别的政治逻辑

The Political Logic of Chinese Official Ranks

by Nie Huihua, Gu Yan

To understand China's political and economic issues, one must first understand how Chinese government officials behave. To understand how officials behave, one must first understand their administrative ranks. The reasons are as follows.

First, in China’s bureaucratic system, administrative rank determines how resources and power are allocated. As a common saying goes, “Higher-ranking officials can easily overpower their subordinates官大一级压死人,” which vividly shows that rank is the explicit rule of the game in the bureaucracy.

Second, almost all officials treat promotion in rank and appointment to more important posts as the core goals of their careers. This is captured by the well-known saying: “A soldier who doesn’t want to become a general is not a good soldier.” It is only by understanding official ranks that one can make sense of the behavioral patterns of local governments and their officials across China.

However, administrative ranks in China’s bureaucracy are highly complex and sometimes not even clearly specified. Ordinary people find them hard to grasp, and even professional scholars like us, who specialize in studying China, often have to spend a great deal of time to sort them out. Although there is plenty of information online, it is either incomplete or inaccurate.

Before we offer a systematic explanation of administrative ranks in Chinese officialdom, readers might like to try answering a few questions about ranks:

What rank is a deputy director-general of the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration? What rank is a deputy head of Baiyun District in Guangzhou? What rank is the director of the Baiyun District education bureau in Guangzhou? What rank is a deputy chief procurator at the Chaoyang District People’s Procuratorate in Beijing?

If you think they are at different ranks, you are wrong. The correct answer is: they are all Division-Head level (正处级) officials. Precisely because the issue of official ranks is both so important and so complex, we feel it is necessary to dedicate an article to explaining the rules of ranks in China’s officialdom.

I. China’s Five-Tier Administrative Hierarchy Defines the Basic Framework of Official Ranks

Typically, the administrative rank of a Chinese official is determined by the administrative rank of the institution where he or she serves. This is the first principle for identifying an official’s rank.

Unlike the organizational structures in most countries, China’s administrative division has five levels:

the central level: nation;

the provincial level: provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the central government;

the prefectural level: prefecture-level cities, prefectures, autonomous prefectures and leagues;

the county level: counties, districts, banners and county-level cities; and

the township level: townships, towns and sub-districts.

Accordingly, officials are grouped into five main rank categories, and each category is further divided into two sub-ranks: a principal rank (正职) and a deputy rank (副职). Together, these ten sub-ranks form the basic framework for identifying an official’s status. The breakdown is as follows:

1. National level (国家级正职)

This includes the top leaders of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the state. Positions at this level comprise:

General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee; Member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee; President of China; Chairperson of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC); Premier of the State Council; Chairperson of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), and Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC).

2. Deputy-national level (国家级副职)

This covers members of CPC and state’s top leading bodies other than those at the national level, as well as the deputies to the national-level positions. They include:

Members and alternate members of the CPC Central Politburo, Member of the Secretariat of the CPC Central Committee, Vice Chairpersons of the NPC Standing Committee, Vice Premiers and State Councilors of the State Council, Vice Chairpersons of the CPPCC National Committee, President of the Supreme People’s Court, and Procurator-General of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate.

Special cases involve the Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) and the Secretary of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission (PLAC), whose rank depends on specific circumstances.

According to a second principle of identifying official ranks -- known as the “highest applicable rank” principle -- if these two secretaries are member of the the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, they hold a national-level rank. If they are only member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, they hold a deputy-national-level rank.

3. Provincial-Ministerial level (省部级正职)

This includes the "number one" leaders of central ministries and of provincial-level Party committee and government. They include:

–– Principal leaders of working bodies under the CPC Central Committee (such as the Policy Research Office, the Party History Research Centre and the Party Literature Research Centre);

–– Principal leaders of the constituent departments of the State Council (ministries, commissions, offices, etc.);

–– Principal leaders of the working bodies and special committees under the NPC and the CPPCC; and

–– Principal leaders of the “four leading bodies” (Party committee, people’s congress, government and CPPCC committee) in each provincial-level region.

Still applying the “highest applicable rank” principle, Wang Huning王沪宁 was at the provincial-ministerial level when he served as Director of the CPC Central Policy Research Office from 2002-2007; after 2007, he was promoted successively to Secretary of the CPC Central Secretariat and then Member of the Secretariat of the CPC Central Committee, while still concurrently serving as Director of the Policy Research Office, at which point his rank became deputy-national level.

4. Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level (省部级副职)

This category includes the deputies to the positions listed above at the provincial–ministerial level, as well as members of the Standing Committee of Provincial Party Committees (lists not repeated here).

5. Bureau-Director level (厅局级正职)

This category includes:

–– Principal leaders of departments and bureaus under central ministries and commissions;

–– Principal leaders of departments, bureaus and commissions directly under provincial governments; and

–– Principal leaders of the “four leading bodies” (Party committee, people’s congress, government and CPPCC committee) of prefecture-level cities, including prefectures and districts under centrally-administered municipalities.

6. Deputy-Bureau-Director level (厅局级副职)

This includes the deputies to bureau-director level posts, as well as members of the standing committees of prefecture-level Party committees.

7. Division-Head level (县处级正职)

This category includes:

–– Principal leaders of divisions under central ministries and commissions;

–– Principal leaders of departments, bureaus and commissions directly under provincial governments;

–– Principal leaders of commissions, offices and bureaus under prefecture-level cities

–– Principal Party and government leaders of townships or sub-districts in centrally-administered municipalities

–– Principal leaders of the “four leading bodies” (Party committee, people’s congress, government and CPPCC committee) of counties

8. Deputy-Division-Head level (县处级副职)

This includes the deputies to principal division-head-level positions and members of the standing committees of county Party committees.

9. Section-Head level (乡科级正职)

This category includes:

–– Principal leaders of sections in organs under prefecture-level cities

–– Principal leaders of commissions, offices and bureaus under county governments

–– Township Party secretaries, township heads and chairpersons of township people’s congresses

–– Secretaries of sub-district working committees and directors of sub-district offices

10. Deputy-Section-Head level (乡科级副职)

This includes the deputies to principal section-head-level positions, as well as members of township Party committees and members of sub-district working committees.

With this basic framework, the rank of most officials can be identified.

For example, the head of the State Administration for Market Regulation, the Secretary of the CPC Zhejiang Provincial Committee, and the Mayor of Beijing are all at the Provincial-Ministerial level.

The head of Chaoyang District in Beijing, the Director of the Zhejiang Provincial Development and Reform Commission, and the Chairperson of the CPPCC Fuzhou Municipal Committee in Jiangxi Province are all at the Bureau-Director level.

The directors of sub-district offices (or township heads) in Chaoyang District of Beijing, the Director of the General Affairs Division of the Zhejiang Provincial Development and Reform Commission, and the head of Linchuan District of Fuzhou City in Jiangxi Province are at the Division-Head level.

According to the first principle — the administrative rank of a Chinese official is determined by the administrative rank of the institution where he or she serves — Nanchang in Jiangxi Province is a prefecture-level city, so in principle the Secretary of the CPC Nanchang Municipal Committee should be at the Bureau-Director level. However, the Party Secretary of Nanchang also serves a member of the Standing Committee of the CPC Jiangxi Provincial Committee. Under the second “highest applicable rank” principle, this makes him/her a Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level official.

II. Special Systems Beyond the Five-Tier Administrative Hierarchy

While the administrative ranks of most officials can be identified using the benchmark system, the status of many others cannot be determined by simply applying the above system. This is because their affiliated institutions do not belong to any of the five administrative tiers but fall between two levels; that is, the institutions themselves are at the Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level, Deputy-Bureau-Director level, or Deputy-Division-Head level. Consequently, the principal leaders of these institutions hold a rank half a step higher than the level of their administrative region.

(1) The first special case involves certain units managed by the State Council or its ministries/commissions, which are Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level, instead of ordinary ministerial-level units.

Examples include the National Bureau of Statistics国家统计局 and the Government Offices Administration国家机关事务管理局 directly under the State Council, as well as bureaus managed by State Council ministries/commissions, such as the National Energy Administration国家能源局 and the National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration国家粮食和物资储备局 (both managed by the National Development and Reform Commission), and the National Tobacco Monopoly Administration国家烟草专卖局 (managed by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology).

A simple way to identify them is: units with “总局” in their name are ministerial-level units (such as 国家市场监督管理总局 State Administration for Market Regulation); those named “国家...局”(state administrations and bureaus under the ministries and commissions) are sub-ministerial level; and units without the “National国家” prefix are generally bureau-director level units within ministries/commissions.

For instance, when the State Administration of Work Safety国家安全生产监督管理局 was established in 2001 under the State Economic and Trade Commission, it was a sub-ministerial level unit. In 2003, it became an institution directly under the State Council (remaining deputy-ministerial), and in 2005, it was upgraded to the State Administration of Work Safety国家安全生产监督管理总局 (a ministerial-level institution). This institutional evolution also reflects the central government’s increasing emphasis on work safety.

Since “国家...局” are deputy-ministerial-level units, the middle and senior ranks of their cadres are half a grade lower than their counterparts with the same titles in ministerial-level bodies.

According to the State Council General Office’s “Notice on Printing and Distributing Three Implementation Measures for Reforming the Pay System in Party and Government Organs and Public Institutions”, in a “国家...局”, its director, deputy director, department director-general, and deputy department director-general correspond respectively to the rank of a vice minister, a department director-general, a deputy department director-general and a division chief in a ministry or commission, while the ranks below division chief are the same in both systems.

This means, for instance, that a deputy department director in the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration actually holds division-level rank, and the division chiefs under that department are also at division level. Although a deputy department director and a division chief hold the same administrative rank, the former leads the latter in business terms and will usually be promoted before the latter.

One point should be noted: while “国家...局” exist at the central level, localities cannot set up “国家...局” of their own. Therefore, the branches of “国家...局” in the provinces are treated in the same way as other provincial departments and bureaus, and are all at department–director level. For example, the Director of the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration is at vice-ministerial level, and the directors of provincial tobacco administration are department–director-level officials.

(2) The second special case concerns China’s fifteen sub-provincial cities: Harbin, Changchun, Shenyang, Dalian, Qingdao, Nanjing, Ningbo, Xiamen, Wuhan, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Chengdu,Xi’an, Jinan and Hangzhou.

According to the Opinions on Several Issues Concerning Sub-provincial Cities关于副省级市若干问题的意见 issued by the Office of Central Institutional Organization Commission in 1995, the rank of organs directly under sub-provincial city governments should be determined by analogy with “国家...局”: municipal working departments are Deputy-Bureau-Director level, and their internal units are Division-Head level.

The rank of urban districts and their departments is set by reference to the corresponding relationship with the municipal organs; counties and county-level cities under the jurisdiction of a sub-provincial city remain at county level, and their departments are Section-Head level.

In practical terms, this means that the Mayor of Guangzhou is at Sub-Provincial (Ministerial) level, the vice mayors are at Bureau-Director level, the Director of the Guangzhou Municipal Education Bureau and the head of Baiyun District are both at Deputy-Bureau-Director level, and both the deputy head of Baiyun District and the Director of the Baiyun District Education Bureau are at Division-Head level.

As above mentioned, although the deputy head of Baiyun District and the district education bureau director hold the same administrative rank, the former leads the latter in the business.

(3) The third special case is that the procuratorates and courts hold an administrative rank half a grade higher than the government departments of the same locality. This is because the local government, procuratorate, and court are all state organs elected by the local People’s Congress, the so-called “一府两院”.

For example, the Mayor of Beijing is at the Provincial-Ministerial level, the Chief of Chaoyang District in Beijing is at the Bureau-Director level, and the Director of the Chaoyang District Finance Bureau is at Division-Head level. Therefore, the Chief Procurator of the Chaoyang District People’s Procuratorate, being half a grade higher than the District Finance Bureau Director, is at Deputy-Bureau-Director level.

By extension, a Deputy Chief Procurator of the Chaoyang District People’s Procuratorate is at Division-Head level, and the Chief of the Public Prosecutions Department within that procuratorate is actually at Deputy-Division-Head level.

III. Party-People Organizations: Mutual Influence between Official and Institution Ranks

In China, the ruling party leads the state, so in actual political practice the heads of Party organs usually rank higher than the heads of government departments at the same territorial level. This is mainly achieved through the standing committees of Party committees at each level.

As described in the basic framework above, members of a Party committee’s standing committee, apart from the principal leaders of the “four leading bodies” (Party committee, people’s congress, government and CPPCC committee), are half a rank lower than the administrative level of the locality but half a rank higher than the departments they are in charge of.

For example, in a prefecture-level city, a member of the municipal Party committee’s standing committee who concurrently serves as head of the Publicity Department holds Deputy-Bureau-Director level rank, which is half a grade above the director of the municipal bureau of culture, who is at Division-Head level.

The key question is: who can sit on the Party committee’s standing committee?

In addition to the Party secretary (provincial Party secretary, municipal Party secretary or county Party secretary), the principal government leader (governor, mayor or county head), the full-time deputy Party secretary, the secretary of the commission for discipline inspection, the secretary of the political and legal affairs commission, the head of the organization department, the head of the publicity department, the executive vice head of government (executive vice governor, executive deputy mayor or executive deputy county head), the secretary-general of the Party committee, and the commander or political commissar of the local military district are all standing committee members.

The head of the united-front work department and the Party secretary of the provincial capital city are generally standing committee members as well. For a period of time, the chairperson of the provincial CPPCC committee also sat on the provincial Party standing committee (at present this is no longer the case).

The composition of the standing committee shows that the overwhelming majority of its members are in fact heads of subordinate Party organs.

Because the rank of the “number one” leader in turn affects the rank of the organ he or she heads, Party organs in practice are half a rank higher than the corresponding government departments. This also means that the deputy heads of Party organs can be half a rank higher than their counterparts in government departments.

For example, the head of the Organization Department of a provincial Party committee is certainly a member of the provincial Party standing committee and therefore a Sub-Provincial (Ministerial) level cadre. The executive deputy head of that Organization Department, who is in charge of day-to-day work, is then a Bureau-Director level cadre, on the same rank as the director of the provincial human resources and social security department.

In fact, almost all provincial human resources and social security department directors concurrently serve as deputy heads of the provincial Party committee’s Organization Department. Ordinary deputy heads of the Organization Department, however, have the same administrative rank as deputy directors of the human resources and social security department.

Party organs are also half a rank higher for another reason: the nature of these bodies.

Under the CPC Constitution, commissions for discipline inspection at all levels, like the full Party committees at the same level, are elected by Party congresses at the corresponding level. As a result, the discipline inspection commissions rank half a level above other subordinate Party departments (the organization, publicity and united front work departments) and above government departments.

For example, the Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection is at Deputy-national level (if he is a member of the Political Bureau) or at National level (if he is a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau). The deputy secretaries of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection are at Provincial-Ministerial level, and the heads of its Organization Department and Publicity Department are at Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level.

Following the same logic, the director of the Office for Corruption Prevention of a provincial commission for discipline inspection holds Deputy-Bureau-Director level rank, whereas the director of the research office of a provincial Party committee’s Organization Department or the director of the general office of a provincial human resources and social security department is at Division-Head level.

In addition to Party organs, there are also people’s organizations such as trade unions, the Communist Youth League, women’s federations and federations of industry and commerce. All of these are led by the Party and are therefore collectively known as Party-people organizations. At each level, Party-people organizations have the same administrative rank as the corresponding subordinate government departments.

IV. Special Positions, Over-Ranking Cadres, and Other Institutions

Beyond the leadership positions with titles “长“ like “Chief” or “Director” (e.g., Governor, Bureau Director, Division Chief), China also has a system of non-leadership positions.

These primarily comprise three tiers, each with principal and deputy levels: Counselor巡视员 (corresponding to Bureau-Director level), Consultant调研员 (corresponding to Division-Head level), and Principal Staff Member主任科员 (corresponding to Section-Head level).

Non-leadership positions generally do not possess decision-making or signing authority unless delegated by the principal leader. Additionally, there are Inspector positions督察专员 within central ministries/commissions, such as the National Chief Inspector of Education and the Chief Land Inspector, who are typically at the Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level.

A second category of special positions is assistant ministers in central ministries and commissions. The Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Commerce, for example, have several assistant ministers, who also serve concurrently as members of the ministry’s leading Party members’ group.

The title “assistant” is not part of the standard rank sequence. In rank terms, assistant ministers fall between a vice minister and a department–bureau-level director; administratively they are usually at Bureau-Director level, but they enjoy vice-ministerial benefits, including in political status, medical care and housing. The ranks of Assistant Chiefs of government at the provincial, city, and county levels follow this analogy.

Beyond the regular hierarchical system, there are also officials whose personal rank is higher than the standard rank of their institution; this arrangement is known as “over-ranking” 高配. There are three main types.

First, leaders of key ministries and commissions. For example, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) has six deputy directors who hold Provincial-Ministerial level rank, and the Ministry of Public Security has two vice ministers at Provincial-Ministerial level rank, indicating their significant influence.

Locally, the head of the Public Security Bureau is usually a member of the Party Committee Standing Committee and/or a Deputy Chief of the government, placing them half a step higher than the principal leaders of other government departments.

Second, important internal organs within departments. These include, for example, the enforcement bureaus of people’s courts, the anti-corruption bureaus of people’s procuratorates, and the Political Departments of quasi-paramilitary organs such as public security, procuratorates, courts and justice departments. The principal leaders of these internal organs are considered part of the deputy leadership sequence of their parent institution, and therefore rank half a level higher than the heads of ordinary internal departments.

Third, leaders of economic development zones, certain counties directly administered by provincial governments, and some county-level cities, who generally hold a rank half a level higher than they would under the basic framework. For instance, the director of the administrative committee of a provincial-level economic development zone or high-tech zone is typically at Deputy-Provincial (Ministerial) level. The Party Committee Secretary and Mayor of Yiwu City, administered by Jinhua City in Zhejiang Province, are both at Deputy-Bureau-Director level.

In addition to Party and government organs and people’s organizations, China also has a vast number of public institutions, such as universities, hospitals, newspapers and libraries. Many of these bodies partly follow the same ranking system as Party and government organs, and their administrative level is determined by their subordination.

For instance, most “Project 985” universities (over 30) are directly administered by the central government and are thus at the vice-ministerial/provincial level. Their University President and Party Committee Secretary are at the Sub-Provincial (Ministerial) level; their Executive Vice Presidents and Executive Deputy Party Committee Secretaries are at the Bureau-Director level; other Vice Presidents/Vice Secretaries are at the Deputy-Bureau-Director level; and the heads of university departments, divisions, and schools (colleges) are at Division-Head level.

Ordinary undergraduate universities are generally administered by provincial education departments and are themselves at Bureau-Director level; the ranks of their vice-presidential leadership and of the heads of departments, offices and schools correspond to those of equivalent posts in centrally administered universities.

Standard undergraduate universities are generally managed by provincial education departments and are at the departmental/bureau level, with the ranks of their Vice Presidents, department/division heads, and school deans corresponding to those in centrally administered universities.

Newspaper organizations have administrative ranks similar to those of government departments. For example, Xinhua News Agency and People’s Daily, which are directly administered by the central authorities, are ministerial-level institutions, and their principal leaders are therefore at Provincial-Ministerial level.

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) also possess administrative levels, as their leaders are assigned corresponding ranks. There are over 50 central SOEs whose personnel affairs are managed by the Central Organization Department; their principal leaders are generally at the Sub-Provincial (Ministerial) level, with a very few at the Provincial-Ministerial level (e.g., the former China Railway Corporation).

Those whose personnel affairs are managed by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) are at the Bureau-Director level. Similarly, SOEs whose personnel affairs are managed by local Party Committee Organization Departments generally have leaders at the Deputy-Bureau-Director level or Bureau-Director level, while those managed by local SASACs are at the Deputy-Bureau-Director level.

Is it best to see this in a historical context as a communist government, or a traditional Chinese imperial bureaucracy which had some communist influences during the 20th century?