Xu Yangsheng on how western & eastern philosophies shape AI development

Western philosophy focuses rationality & logic, while Eastern thought stresses wholeness & interconnection. The two shape different world models, and AI is, at its core, the business of building them.

Last year, this newsletter ran a piece by Song-chun Zhu, dean of Peking University's Institute for Artificial Intelligence, who cautioned that the narrative surrounding AI in China is misguided. It's a sharp read and I highly recommend it.

Today's piece stays with AI, which highlights the connection between AI and philosophy, and how different philosophical traditions in the West and East have helped shape what AI is built to do.

It is a speech delivered by Dr. Xu Yangsheng, the President of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, at the Long Feng Science Forum on January 24, 2026.

A member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, Xu earned his PhD at the University of Pennsylvania, spent years at Carnegie Mellon University, and later joined The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

In the speech, Prof. Xu noted that Western philosophy, with its emphasis on rationality, logic, and the knowability of an objective world, has nudged AI towards dismantling problems into parts, optimizing efficiency, and building "world models" through technical decomposition.

Eastern philosophy, by contrast, places more weight on wholeness and interconnection, intuitive experience, and ethical value. That tradition, Xu suggests, is a reminder that anything resembling real intelligence cannot be separated from emotional attachment and lived experience, and that the destination should be human–machine coexistence rather than mere performance.

He further noted that AI dominated by data and large language models has hard limits, because even its most basic premises — what counts as intelligence, how behaviour should be judged, and which values systems should be aligned — are, in the end, philosophical questions.

Education, Xu argues, therefore needs to pivot towards cultivating genuinely creative people: those who understand human nature, think independently, develop aesthetic sensibility, and build resilience.

This piece was first published on Prof. Xu's personal WeChat public account. Please note the following translation is my own and has not been reviewed by him.

人工智能与东西方哲学思想

Artificial Intelligence and Eastern–Western Philosophical Thought

Adapted from Professor Xu Yangsheng's keynote speech at the Long Feng Science Forum on January 24, 2026

Xu Yangsheng

Good morning, friends. I'm delighted to have the opportunity to share a few thoughts with you today. Over the past 40 years, my research has focused on artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics. Over time, I've come to realize that AI is deeply intertwined with philosophy, and the stark contrast between Eastern and Western philosophical worldviews makes the development of AI especially fascinating.

When I received the invitation to speak at this Forum, I thought it might be meaningful to reflect briefly on these ideas. What I offer here is neither systematic nor exhaustive, and I can't promise that every point I make is entirely accurate. I simply hope to use this occasion for open exchange, and to learn from all of you.

In my view, both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions have valuable insights to offer AI. For instance: How should a model of the world be constructed? What exactly is intelligence? How should it be measured? What constitutes "good" intelligence? Where should we draw the line between AI and human beings? Should AI behave like the ideal "good child" people envision? And ultimately, is the goal truth, or consensus? If we do not address these fundamental questions first, AI may well head in very different directions.

To begin, let us start with philosophy. Roughly speaking, philosophy consists of three parts:

First, ontology: what the world is.

Second, epistemology: how we come to know the world.

Third, axiology/ethics: how to live in the world — in other words, what the relationships are among people, between people and the world, and between people and nature.

Of course, this is a simplified framework. For example, logic can be placed within epistemology; whether aesthetics counts as philosophy is debated; and as for statistics, some of my friends in mathematics never call statistics “mathematics”, while others treat it as part of mathematics. When I studied statistics, it was indeed taught in a maths course.

I largely taught myself philosophy through reading, even earlier than I began doing scientific research, so it has been about 50 years now. Along the way, I encountered two "wonderful" observations:

First, Eastern and Western philosophical traditions seem to have taken shape at roughly the same time. In the West, there were the Socratic tradition and Jewish thought; in the East, thinkers such as Confucius, Laozi, Mencius, and Zhuangzi; and in India, Gautama Buddha. Much of this activity clustered around 500 BCE. It's remarkable that so much foundational thinking emerged within the same historical window.

Second, the two traditions place their emphasis in different places. Western philosophy tends to focus more on epistemology and ontology, whereas Eastern philosophy leans more towards axiology. It discusses epistemology less, and often with less rigor — though Zhuangzi is an exception.

Why mention this first? Because the development of AI touches all three parts of philosophy at once.

Let me briefly share some differences in each part.

Start with ontology. Western ontology tends to emphasize rationality, objectivity, certainty, and knowability. By "knowable", I mean the belief that the world can ultimately be understood and explained clearly. That conviction once gave me enormous encouragement.

Eastern thought, by contrast, is less likely to offer that kind of firm assurance. It places more emphasis on wholeness, dynamism, interconnection, and the idea that all things share a common source. It stresses how parts affect one another: the heart, lungs, stomach, and liver are interconnected; if one room catches fire, the whole house is endangered.

Next, epistemology. At the core of Western epistemology is rational logic. When something happens, it insists on asking "why," and looks for reasons. Eastern approaches to knowledge are often less strict in this respect: they may not feel the same need to argue out why something is so. Among classical Eastern thinkers, Zhuangzi is a notable exception: he still tries, at least in part, to explain why he says what he says.

More broadly, Eastern philosophy places greater weight on intuitive and lived understanding. That kind of understanding matters because, in lived experience, subject and object can meet through resonance and empathy, and emotion is bound up with the "heart-mind." From this perspective, truth is grasped directly: not produced by analysis, not assembled from data, and not dissected by linguistic logic, but experienced.

Take a simple example: imagine I'm a woman, I see a man, and I fall in love. It begins with intuition. There may be no clear logic to it, and it can be hard to explain "why I love him." Language cannot fully account for it.

You may know that the current wave of AI took off with large language models. But what I want to emphasize today is this: language is not all-powerful. Language matters, but it is still a long way from intelligence. What we might call "real truth" is often extraordinarily difficult to put into words. That is one reason mathematics is so important, though you could argue that mathematics is also a kind of language, and it isn't omnipotent either.

My students sometimes say to me, "Sorry, Professor, I may not have explained it clearly." And I reply, "You explained it very clearly. The problem is that you used language, and some things simply aren't meant to be fully captured by language."

Beauty is like that, too. Watch two minutes of mime: not a single word, and yet you still understand. And what's more, each person feels something slightly different. So language is not all-powerful.

Experience is crucial as well, and Eastern philosophy places great weight on experience. This morning, as I walked beside a fishpond, I kept wondering: does a fish know how humans walk? Could it understand the pain and joy of walking? Of course you can't demand that of a fish, because it lacks that kind of experience. In the same way, humans cannot truly experience the pain and joy of birds. People often say that birds sing every day, so they must be"happy", but do we actually know that they are?

If AI never reaches the level of experience, it will not achieve genuine intelligence. That is one of the insights I have drawn from Eastern philosophy.

Finally, let me turn to axiology.

In the Western tradition, questions of "value" often come back to a single core issue: what is the meaning of human life in the world? What are we ultimately pursuing? Western thought tends to place priority on truth. Eastern thought, by contrast, tends to place priority on goodness, aiming at the cultivation and perfection of life itself. These are different perspectives, and together they make up the richness of human intelligence.

Let me illustrate this with a story.

One morning, two young monks are walking through a monastery courtyard when they see a snake swallowing a frog. Monk A drives the snake away, feeling that this is a sin. Monk B objects, arguing that interfering is itself wrong: snakes survive by eating frogs — can you possibly stop them all? Unsure, they ask an elder monk to judge who is right.

The elder monk replies that Monk A is right, because he is compassionate. But Monk B is also right, because he lets go of attachment, respects the laws of nature, and understands that if the snake does not eat frogs, it too will die.

One emphasizes compassion; the other emphasizes letting go. Buddhism tends to value the former, while Daoism tends to value the latter. One reflects the beauty of purposeful action (有为); the other reveals the insight of non-action (无为). Zen brings these two together at their point of intersection, and this is characteristic of Eastern philosophy.

From a more typical Western philosophical perspective, such ambiguity is harder to accept: if Monk A is right, then Monk B must be wrong; if Monk B is right, then Monk A must be wrong.

Friends, standards of right and wrong, good and bad differ, and that has a great deal to do with the direction of AI, large language models, and world models.

Broadly speaking, Western thought tends to approach the world as a collection of things. Many chemists are here today, and chemistry is a good example: it often treats everything as an object composed of molecules and atoms. A wooden table has a chemical structure that can be analyzed and quantified. The human body, too, can be examined in the same way. Anything material can be studied through this lens.

In the Eastern view, the world is approached more as "persons": objects can have “heart”, and emotion is taken seriously.

To put it another way: from a Western philosophical perspective, "things" exist and operate according to certain laws. Humans are living organisms; we must eat to survive; digestion requires a stomach. Pigs are living organisms as well, so they also have stomachs. In that sense, a pig's stomach and a human stomach serve the same basic function. The same logic can be extended to cats, rabbits, snakes, and so on. Western thinking often seeks a single, unified framework that can explain all phenomena.

From an Eastern philosophical perspective, by contrast, heaven and humanity form a unity, and each thing is understood to have its own "heart." When winter comes and the wind turns cold, leaves fall because the tree "feels" the cold. If fruit "feels" the cold, it may fail to ripen.

There is a line from Zhuangzi庄子 that I especially like: "物物而不物于物,念念而不念于念." As I understand it, to deal with things does not mean treating material objects as cold, lifeless "things," which misses part of their reality. And to attend to thoughts does not mean clinging to thoughts as fixed objects, otherwise the task becomes impossible.

In other words, "应无所住,而生其心": when the mind becomes fixated, effort turns forced, and that very fixation becomes the obstacle. This is a distinctly Eastern way of thinking.

A moment ago, I mentioned the Eastern idea that "objects have heart". But where, exactly, is this "heart"? I wrestled with this question for many years — about thirteen, in fact — while spending long hours in old bookshops in Hong Kong.

Let's begin with the formation of Chinese characters. Around the Shang dynasty, roughly 1300 BCE, many characters referring to body parts were written with the radical 月, which originally meant "flesh." This includes characters for the liver肝, gallbladder胆, stomach胃, abdomen腹, foot脚, and so on. There is only one notable exception: the character 心, the heart.

I study calligraphy, and I know that when the character 心 was first created, it did not contain the radical 月. Over time, its script evolved into the shape we recognize today, with two dots.

This raises an intriguing question: after more than 3,300 years, what do these two dots in 心 represent? The inner dot presumably refers to the biological heart inside the body, but where is the outer dot?

Now consider a group of characters related to 心: 愛 (love), 恨 (hate), 思 (think), 怨 (resent), 性 (nature or disposition). You may notice that characters containing 心 often suggest two "endpoints." When these characters are used as verbs, they are frequently transitive: to love or to hate, you must love or hate something.

Consider another example. Suppose there is only one mobile phone in the entire world, and it happens to be in your hand, no one else has a phone. Would your phone be useful? It couldn't reach anyone, so in that sense it would be useless. Friends, the "heart" is similar: it requires a second party. Only when there is another endpoint can the heart form a connection. That is what I mean by the "outer dot" in 心.

In this sense, the heart is a connector of all things, and is a basic idea in Eastern philosophy. It is much like the phones we carry today: a phone is a node in a network that connects people to one another.

Eastern and Western philosophies will have a profound influence on the future of AI, as AI contains deep philosophical questions. Philosophers will have plenty to do in the years ahead, provided they are philosophers who genuinely think.

Now let me pose a philosophical question about AI: what is "intelligence"?

From a Western philosophical perspective, "intelligence" is often understood as the technical decomposition and reconstruction. Today's pursuit of artificial general intelligence (AGI) aims to exceed human rational capacity and expand the range of problems that can be solved. In my view, much of this effort is ultimately about improving efficiency.

Take the game of Go as an example. If you can systematically break down your opponent's strategies and possible moves, it becomes easier to defeat them. What once required hundreds or even thousands of hours of practice can now be achieved much more quickly with the help of AI. This approach reflects a Western philosophical tradition that emphasizes decomposition, efficiency, and rational analysis.

In Eastern philosophy, by contrast, intelligence remains closely tied to human nature. Human beings possess inner life and spirituality, and machines should not take "surpassing humans" as their central goal. Instead, humans and machines should coexist. AI, from this perspective, ought to help humans deepen, refine, and enrich lived experience.

So, friends, there is no single, absolute answer to this question. Different perspectives can both be valid. Think of a bottle of water: one person says it is transparent and clear; another says it is cold. Both descriptions are true. This is how Eastern and Western philosophies differ: distinct angles and ways of thinking give rise to different world models.

And AI, at its core, is precisely about building world models.

Twenty years ago, I wrote a book titled Human Behaviour Learning and Transformer. In it, I argued that AI is, in a sense, about recording human behavior and then discovering the intelligence embedded within that behavior. That is roughly the route current AI is taking.

This brings us to two pointed philosophical questions.

First, what kind of intelligence are we actually trying to extract? Skills? Strategies? Memory? Intuition? Logic? Different answers will push AI in completely different directions.

Second, what kind of behavior counts as "good"? Imagine three students — A, B, and C — practicing driving, each taking a turn behind the wheel for ten minutes. An instructor can rank them quickly, but there's an underlying problem: standards vary. Different people use different criteria for "good driving."

In AI, that difference becomes a serious challenge. In a domain like Go, where constraints are tight, boundaries are clear, "good" is easy to define: winning is good, and the rules are explicit. But once you move to broader, more abstract forms of behavior, it becomes hard to set a single standard.

Therefore, if an AI system is built for a narrow domain, many of these issues can be ignored; once you aim for a large-scale world model, you cannot avoid them.

What people call value alignment is, at bottom, an attempt to align standards for what counts as "good." For example, different instructors judging "good driving" may reach very different conclusions. This is not because one is right and the other is wrong, but because their value scales, focal points, and weighting of criteria differ. This is the most common source of disagreement when value alignment is not achieved.

Let me give another example. One many of you will recognize: the Transformer. Suppose I hand you a 100-page report at 10 p.m. and tell you I need a summary tomorrow. Finishing it overnight might be difficult. But if someone has already used colored pens to highlight the key points, your job becomes much easier: you can concentrate on what matters most. That is, in essence, an attention model.

Attention is central to Transformers, and the same idea is now widely used across fields, including autonomous driving, computer vision, speech and language, text processing, and more.

In Eastern philosophy, attention is closely tied to a person's spirit神 and intent意. One's spirit神 is meant to dwell in the heart-mind. When it is present, you can sense your heartbeat and your breathing, and you feel fully alive. When your attention drifts, what pulls it away is sometimes described, in traditional terms, as a "demon" — a demon of the heart.

And when the spirit is no longer "at home," when it has left the body, that is called death. That is why I put up signs on campus that read, "Please don't look at your phone while walking."

So in the age of AI, given the differences between Eastern and Western philosophies, will continued AI development lead to different "sciences"? That may sound a little mysterious. My own view is: science is science. Scientific methods, standards of verification, and underlying logic do not change with region or culture. Many chemists are here today, and I think you would agree: chemistry is chemistry, and there is no such thing as "Shenzhen chemistry" or "Longgang chemistry." (Longgang is a district in the Shenzhen City)

The real issue is this: under different philosophical traditions and value systems, the AI people train may end up looking very different. If AI systems diverge in this way without proper value alignment, the consequences could be very serious.

I know many young people are listening today, so I hope you'll think carefully about this: in the next ten years, social structures, including families, schools, even the shape of work, may change in truly dramatic ways. A friend said to me yesterday that companies today often employ thousands of people, but in the future, "one-person companies" may become common, with teams of only two or three at most. If that happens, families and schools may also be reshaped, and entirely new forms of both may emerge.

The next generation may face questions that are not mainly about careers, income, fame, status, or rank. Many parents ask me what job their child should do, how much they will earn, whether they will become well known, and whether they can keep climbing. But it may be that these are no longer the things young people care about most.

And if those concerns fade, where does the meaning of life come from? Will human beings still have desire? That is an even more fundamental issue.

When I first arrived in the United States, I went to a Ningbo restaurant in Lower Manhattan. The owner asked, "What would you like to eat?" I blurted out, "Ribbonfish." Even I couldn't have explained why I said it. He asked, "How should I cook it?" I answered, "Steamed."

A few days ago, I invited some classmates from Zhejiang to my home. I asked them the same question: "What would you like to eat?" They replied, "Anything."

I was surprised: did they have no desire? If someone is unwilling to make even that kind of choice, with no clear preference, it suggests their sense of desire is weakening. And once humans lose desire, that is not a small matter.

So I suspect a new philosophy will emerge in the future: one that no longer revolves around "success studies" or traditional upward mobility, but instead guides humanity towards new pursuits.

That is why it is even more necessary to cultivate creative talent for the future — not people who only follow standard answers, but people who can raise questions, make choices, and create new goals.

Many people ask me: what will AI replace?

My view is that the most disruptive innovation will be hard for AI to replace. I divide people roughly into three layers.

The top 15 percent are pioneers. AI will not produce an Einstein; when it sees an apple fall, it will not suddenly arrive at the laws of mechanics.

At the other end, the bottom 15% often work in strongly physical, real-world settings, who AI cannot replace either.

The group that AI can most readily replace is the middle 70 percent.

The real problem is that our current education system is training exactly this middle 70 percent.

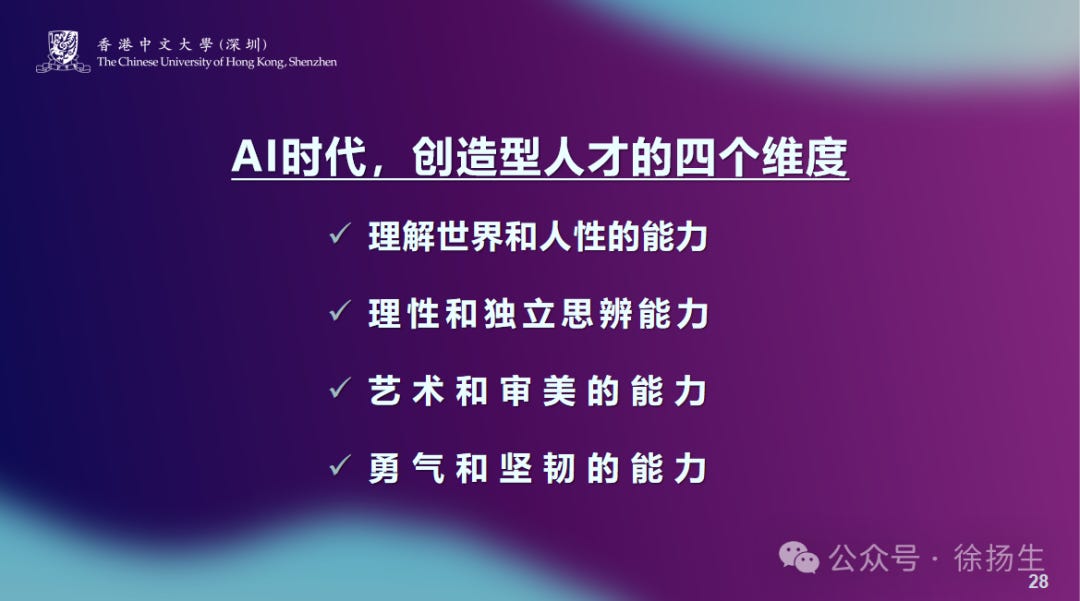

So the focus of education must shift towards cultivating truly creative people. I would describe creative talent in four dimensions.

First, the ability to understand the world and human nature.

To see how the world operates, and to understand human motives, emotions, and behavioral logic. At present, education that builds this ability is widely lacking around the world.

Second, rationality and independent critical thinking.

To reason from evidence, to raise questions, and to form one's own judgement. This is extremely important, but the current education's emphasis on it today is perhaps only 20%, far from enough.

Third, artistic and aesthetic ability.

Schools teach art not to turn every child into an artist, but to raise aesthetic capacity. I have visited a hundred secondary schools. Only about a quarter truly do a decent job with art classes; most essentially do not teach it.

Without aesthetic capacity, life loses an essential support. What ultimately supports a person in life? I think at least two things: beauty — because the world contains so much of it; and love — because there are people who love me, and people whom I love. Both are related to art. If you do not understand art, it can be difficult to understand beauty and love, and the emotional world can easily become hollow.

Fourth, courage and resilience.

If a student always gets an A and then receives a B one day, they may collapse, even develop extreme thoughts. That would be tragic. Life is a long process, and setbacks are inevitable. Without resilience, you lose another crucial support, and a single failure can feel like the end of everything.

Friends, many educators today grew up in a highly "rational" world. They teach in rational ways, and as a result, they often underweight the cultivation of these deeper, more foundational capacities.

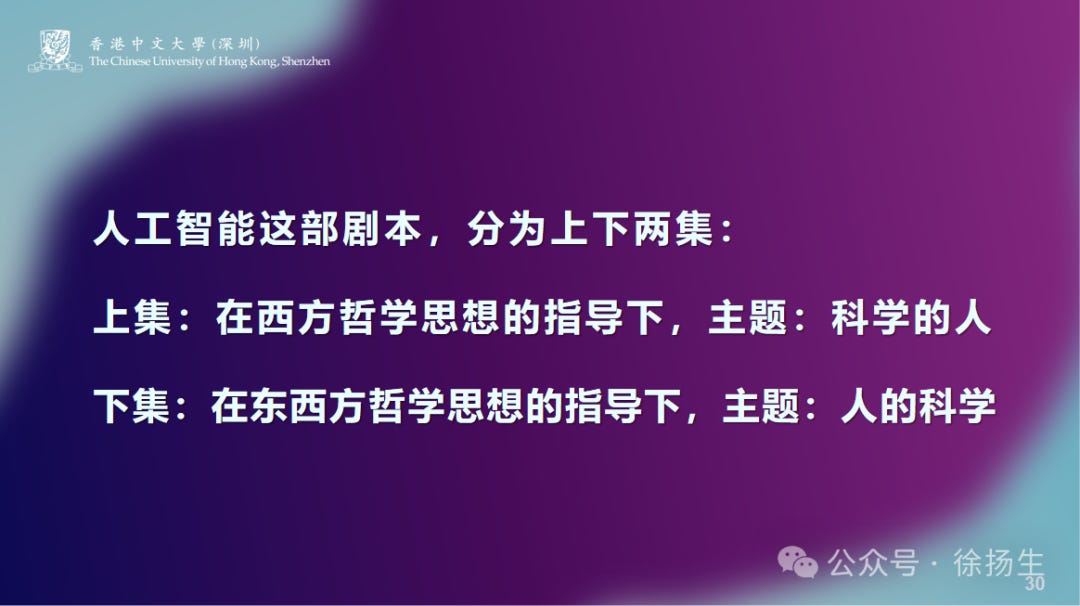

In my view, the final direction of AI is a "science of man".

If AI is compared to a script, I would roughly divide it into two episodes:

Right now, we are still in the first episode, themed "the scientific human". Under the guidance of Western philosophy, humans are treated as objects that can be decomposed, measured, and modeled. "Rational" and "scientific" methods are used to break down the "human": what is the structure of a hand? what functions does it have? what cells is it made of? where is its power source? can a hand be built to resemble a human hand? Other organs are approached the same way, using what we regard as "scientific" methods to study the human as a material object.

In the end, I believe the second episode will arrive. Under the combined guidance of Eastern and Western philosophies, the theme will move towards "a science of man". In other words, humans are not merely objects of study; humans themselves become the core of science.

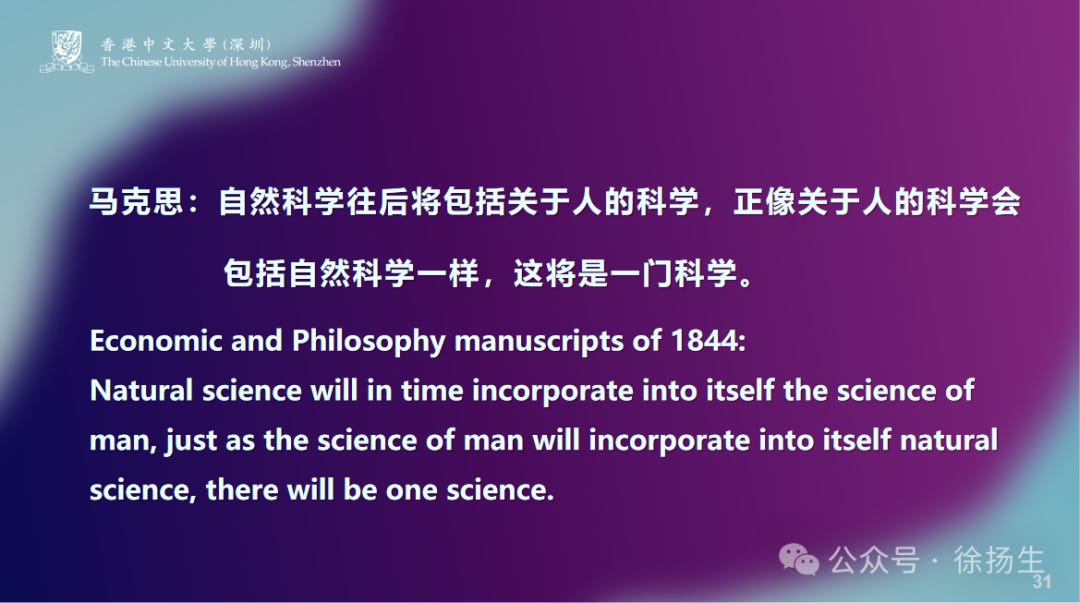

This is not something I am inventing out of thin air. As early as 180 years ago, Karl Marx, in his 1844 Economic and Philosophy Manuscripts, put forward a remarkably forward-looking idea: Natural science will in time incorporate into itself the science of man, just as the science of man will incorporate into itself natural science, there will be one science.

I believe AI will ultimately move in this direction: from "treating humans as objects" to "truly understanding what humans are". Only then can AI go genuinely deeper. Enditem

YuZhe - In thinking about the difference in the training data for both US and Chinese LLMs, I'm wondering your take on the concept of AGI?