Negligible corporate-to-household dividends are China's top consumption bottleneck: economists

Another critical issue is the severe wealth gap, with the top 20% controlling 80% of savings.

Last month, your host explored the topic of income distribution but soon realized many critical issues needed deeper analysis. Today, let's push this discussion further.

Before diving in, here is the conclusion on China's distribution system drawn from recent findings by several leading economists:

Principal issue: China's consumption gap is driven primarily by an imbalanced income flow—corporate dividends to households remain disproportionately low.

Secondary issue: Household wealth inequality, with the top 20% controlling 80% of savings, is significant as well, leaving most financially constrained or indebted.

The central government, it seems, has recognized these issues — just look at how official policy language has evolved:

At the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party (CPC) of China in 2017, President Xi Jinping said:

拓宽居民劳动收入和财产性收入渠道。

We will expand the channels for people to make work-based earnings and property income.

By the 20th CPC National Congress in 2022, the policy focus sharpened explicitly towards lower- and middle-income groups and property-derived earnings:

完善按要素分配政策制度,探索多种渠道增加中低收入群众要素收入,多渠道增加城乡居民财产性收入。

We will improve the policy system for distribution based on factors of production, explore multiple avenues to enable the low- and middle-income groups to earn more from production factors, and increase the property income of urban and rural residents through more channels.

Below, you'll find introductions to several prominent economists and selected excerpts of their research findings. Please note these translations have not been reviewed by the economists themselves.

I. Liu Shijin (刘世锦), Former Vice President (Vice Minister) of the Development Research Center of the State Council

In his recent piece, Liu said:

Analyzing China's 2022 flow-of-funds data reveals that household disposable income is not particularly low. In 2022, China's GDP reached roughly RMB 120 trillion, with adjusted household disposable income at RMB 80 trillion—about 66% of GDP, comparable to developed economies. Of this, RMB 53 trillion was consumed, and RMB 27 trillion was saved (half of national savings, the other half from enterprises). This indicates that Chinese households maintain a relatively high savings rate (around one-third) and a consumption rate of roughly two-thirds.

The core issue is the extreme concentration of household savings: according to China Merchants Bank's "Sunflower Client" report (covering clients with bank assets exceeding RMB 500,000), 20% of depositors control 80% of savings—a figure that may even be understated. This indicates severe wealth inequality, limiting the majority’s savings capacity and leaving many low-income groups in net debt.

Corporate savings are also high, totaling RMB 27 trillion in 2022, with two-thirds held by state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Asset returns from SOEs mainly flow back into savings and investments rather than consumption, structurally suppressing China’s consumption rate. Additionally, China's total net assets reached RMB 756 trillion in 2022, with government assets accounting for RMB 291 trillion (38%), substantially above the global average of under 10%, sometimes negative.

…

For instance, transferring a portion of state-owned equity to social security funds, especially the Basic Pension Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents, and using returns from these assets for expenditures, could transform "non-consumable" assets into consumable resources. In fact, the assets remain the same, only ownership shifts. Structural improvement can thus be achieved simply by reallocating state-owned capital, without altering the total asset volume.

II. Lu Zhe (芦哲), Chief Economist at Soochow Securities

Dr. Lu recently conducted a cross-country comparative study, drawing on a sample of 38 countries, including three Asian nations, 27 European Union member states, major North American countries, and selected countries from Latin America and Africa.

The study finds that:

The proportion of disposable income to GDP among Chinese residents is slightly higher than the average across the 38-country sample. In 2022, the share of household disposable income in GDP stood at 60% in China, compared to the 38-country average of 58%. This finding diverges from some perspectives commonly seen in the media, where it is often argued that Chinese households have relatively low disposable incomes, leading to a lower consumption rate. In reality, this viewpoint is somewhat misleading, for two main reasons:

First, there is a sampling bias. Countries often compared to China are typically advanced economies with high household income shares, such as the US (75%), Japan (63%), the UK (63%), France (64%), and Germany (63%). Compared to these, China's 60% share of disposable income appears lower. However, when the comparison is broadened to include the four Nordic countries, their average is only 46%, and the EU average is 59%—both below China. Therefore, while China's ratio is lower than a handful of leading economies, it is not disadvantaged when compared to the EU or the broader 38-country sample. This underscores the importance of how comparison samples are chosen.

Second, there is an issue of measurement standards. Significant gaps exist between disposable income figures calculated from micro-level versus macro-level data. Many analyses use micro-level figures, which, for 2022, were 20 trillion yuan lower than the macro-level total. Based on National Bureau of Statistics micro data, per capita disposable income in 2022 was 36,800 yuan; multiplied by China's population of 1.41 billion, this yields a total household income of approximately 52 trillion yuan, compared to a GDP of around 120 trillion yuan. As such, disposable income accounts for only 43% of GDP by the micro measure, versus 60% by the macro measure—a 17-point difference. For consistency, these two approaches cannot be mixed; therefore, this analysis relies on macro-level measures.

…

Given that China's share of disposable income to GDP is at a reasonable level, what then explains the relatively low consumption rate? The issue lies in the processes of primary and secondary income distribution.

China's primary distribution accounts for 61.4% of GDP, slightly below the 38-country average of 63.2%. Primary distribution includes net property income, labor compensation, and operating surplus. Compared to the sample average, China's net property income is relatively low, while the share of labor compensation is notably higher—52.4% (China) versus the 38-country average of 43%. Although some statistical discrepancies exist, such as the classification of self-employed income, labor compensation in China remains within a reasonable range overall.

As a result, net property income is the key factor reducing China's primary distribution ratio in GDP, while labor compensation actually boosts it.

Property income in China is relatively undiversified, relying mainly on deposit interest, while corporate dividends to households are far below the global average. About 80% of net property income comes from interest, and only 10% from dividends, compared to a 55% average dividend share among the other 38 countries. This gap is why China has recently emphasized indicators like dividend yield and payout ratios.

In terms of secondary distribution, China performs better than the 38-country average: transfer payments account for -1.4% of GDP, compared to an average of -5%.

This mainly stems from relatively low individual income and property tax burdens. Income and property taxes together account for only 1.2% of GDP, similar to many Latin American countries but much lower than developed nations like the United States. At the same time, net social security income for Chinese households is relatively low, with limited coverage—particularly for rural pensions. Amid ongoing external trade shocks and rising unemployment uncertainty, consumption is significantly influenced by the structure of the social security system.

Overall household income is near the average, but most households earn relatively modest incomes. Income and property taxes mainly target middle- and high-income groups, so their lighter tax burden affects these groups more. Linking income with the distribution system reveals that middle- and high-income earners have the means but a lower propensity to consume, while the majority of residents, though willing to spend, are constrained by limited consumption capacity. For higher-income groups, the core issue is a low consumption propensity; for lower-income groups, consumption is primarily limited by capacity, which depends not only on income from primary distribution but also on purchasing power after secondary distribution.

III. Xu Gao (徐高), Chief Economist of Bank of China International (China) Co., Ltd

Earlier this year, Dr. Xu noted in his personal Wechat blog that:

Returns on capital flow to those who own the capital. Because the corporate sector is the principal holder of capital, it captures the predominant share of these returns. Achieving an optimal consumption share therefore hinges on the household sector’s ability to influence how the corporate sector allocates its capital income. Only if households have a meaningful say—deciding what proportion of corporate capital returns is redistributed to them (thereby becoming household income and consumption) and what proportion is retained for reinvestment—can the use of corporate earnings be aligned with the broader objective of boosting household welfare through economic development. In practical terms, maximizing household welfare requires that households be able to induce firms to transfer income to them whenever the expected return on corporate investment falls to an unacceptably low level.

…

At present, market forces still exert only a limited influence on China's patterns of consumption and investment. Data from the Fourth National Economic Census (2018) show that the corporate sector’s total assets reached RMB 914 trillion that year, of which state-owned enterprises (SOEs) held RMB 475 trillion—52 percent of the total. Although SOEs are nominally owned by the entire population, most of their equity is not held directly by households, so they distribute very little in dividends to consumers. Nor do SOEs remit substantial capital returns to the state. Ministry of Finance figures indicate that, in 2022, state equity in non-financial and financial SOEs totalled RMB 122.3 trillion. Yet only RMB 250.65 billion of the income generated by this capital was transferred to the general public budget. This implies a net cash return on state capital of just 0.2 percent in 2022—hardly impressive. When SOEs channel only limited income to both households and the state, their direct contribution to national consumption is inevitably inadequate.

Moreover, the widespread presence of privately owned firms dominated by a single controlling shareholder also limits the market's ability to balance consumption and investment. Because China's market economy is only about forty years old, equity ownership in private companies is still highly concentrated; many firms are effectively "one-shareholder shows." In such companies, strategic decisions rest almost entirely with the dominant investor and have little to do with the spending power of ordinary households. When those controlling owners focus on building "great enterprises," they tend to plough earnings back into the business rather than support household consumption.

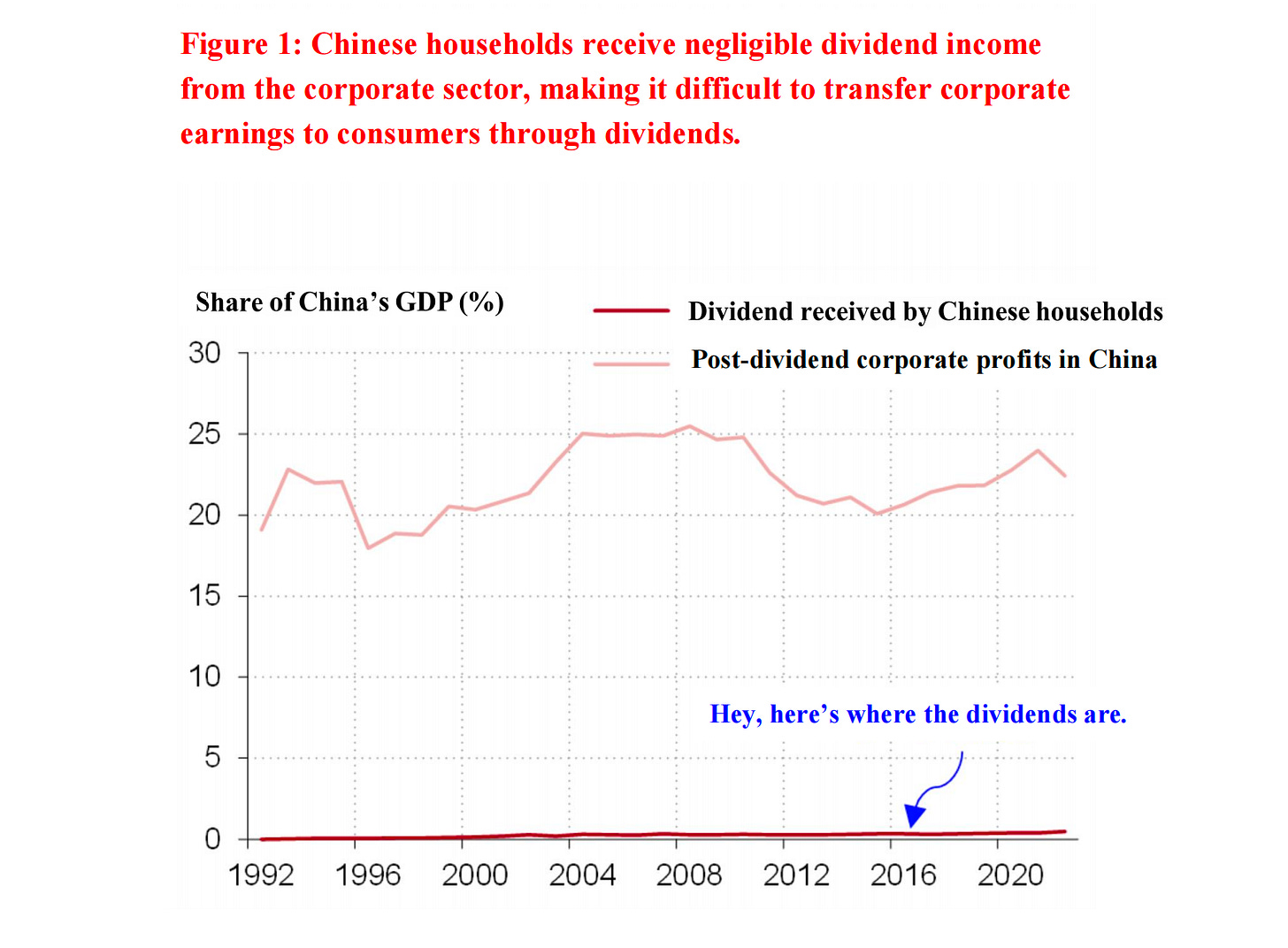

Combined with the constraints already noted for state-owned enterprises, this ownership structure means too little of the corporate sector's income is transferred to households, keeping China's consumption share below the level that would best enhance public welfare. Over the past three decades, dividends paid to households have never exceeded 0.5 percent of GDP—clear evidence of the weak pipeline through which corporate earnings reach consumers. In reality, when investment is already excessive, the most productive "investment" is often no investment at all, but rather redirecting would-be investment income toward consumption. Yet without an effective dividend channel, China has lacked the means to make that shift, resulting in chronic over-investment and under-consumption (see Figure 1).