From liquor to lithium: how China built a battery hub from scratch

Inside the making of the world’s largest single power-battery industrial base: A story of how govt determination in courting talent & capital turned a remote city into a global power battery titan.

Deep in China’s southwestern interior, the city of Yibin — once famous for Wuliangye, the fiery national liquor/baijiu — has reinvented itself into nothing less than the "Power Battery Capital of China."

While Western observers often attribute China's dominance in the field of electric vehicles to opaque state subsidies, today’s newsletter, an excerpt from the book The Heart of Electric Vehicles (电车之心), reveals another aspect: the combination of a local government’s sheer strategic resolve and the region’s unique natural endowments.

Published in August 2025, The Heart of Electric Vehicles bills itself as a "biography" of China’s power battery industry. Its authors, Lu Yang杨璐 and Congzhi Zhang张从志, are reporters at Sanlian Lifeweek, a Beijing-based flagship magazine renowned for its in-depth social and cultural reportage.

Yang has spent nearly two decades covering the rise of domestic brands and supply chains, and Zhang focuses on the intersection of industry and public welfare.

In their account of Yibin’s transformation, what stands out most is the intensity of the city’s determination.

To secure industry giant Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL), officials displayed an extraordinary level of mobilization. For example, they promised and delivered the relocation of ancestral graves within a single week to clear land.

Moreover, the local government offered "mama-style" administrative service, operating less like bureaucrats and more like hungry venture capitalists, even successfully courting top academicians from Tsinghua University to solve talent bottlenecks in a fourth-tier city.

Such "iron will" is further amplified by an objective advantage: abundant hydroelectric power. In a market increasingly sensitive to carbon footprints, Yibin offers manufacturers not just lower costs, but a path to the "zero-carbon" production demanded by global clients.

Since CATL broke ground in Yibin in late 2019, the project has expanded through ten phases. With a planned total capacity exceeding 300 GWh, it has cemented Yibin’s status as the site of the world’s largest single power-battery industrial base.

The following is an abridged excerpt from Chapter 5 of The Heart of Electric Vehicles.

Please note the translation is my own and has not been reviewed by the authors.

宜宾,从白酒名城到动力电池之都

Yibin, from a famous liquor city to a power-battery capital

Upstream on the Yangtze River, more than 1,000 kilometers away from Changzhou, east China's Jiangsu Province, sits Yibin, a city long known for Wuliangye, China’s famous liquor. It has now been awarded the title “China’s Power Battery Capital” by the China National Light Industry Council.

Step out of Yibin Wuliangye Airport and a strong aroma of fermentation hangs in the air. While the scent of liquor still lingers, the Sanjiang New Area on the outskirts of Yibin comes into view. In the misty humidity, rows of silvery power-battery factories stretch on and on, as far as the eye can see.

At the end of 2019, Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL) began construction of its battery plant here. It has now signed projects through Phase 10, with a planned total capacity of more than 300 GWh, making this currently the world’s largest single power-battery industrial base project.

Unlike Changzhou, when Yibin entered the lithium industry, the market outline was already distinct, and the industry hierarchy was largely settled; everyone seemed to be waiting on the eve of take-off. Yibin was like a child standing outside a shop window, staring at a Lego set called “China’s Power Battery Capital,” needing to assemble it brick by brick.

The most important brick, of course, was CATL. In September 2019, CATL and the Yibin municipal government signed an investment agreement and set up a wholly owned subsidiary, Sichuan Contemporary Amperex Technology Limited (SCATL). The plan was to invest RMB 10 billion to build a power-battery production base in Yibin, while also signing an agreement to land the first-phase project of 15 GWh.

Compared with Changzhou back then, Yibin faced fiercer competition at this point. Zhou Qiang, head of the Power Battery Division I at Yibin’s Bureau of Economic Cooperation and Emerging Industries, recalled: “Back then, the cities competing with us, just within Sichuan Province alone, there were three or four, not to mention nationwide. Even Beijing wanted to bring them in. Once, when we went on a business trip to a first-tier city and met comrades there, they were incredibly envious of us, saying, ‘We didn’t manage to recruit CATL, but you guys pulled it off.’”

At the time of signing, it was said that the Yibin municipal government issued a strict commitment, promising to provide at least 500 mu (roughly 82.4 acres) of levelled land within three months. Back then, that land was criss-crossed with gullies, and some plots still had villagers living on them.

Zhou Qiang said: “After the signing, we came back immediately to arrange the work. This area was then called the Lingang Economic Development Zone. Cadres from every sub-district office and neighborhood committee were sent to the countryside, each assigned to specific villages and households to do the persuasion work.

There were also 60 ancestral graves on that 500 mu of land. Relocating graves is extremely difficult, but we moved them within a week. We mobilized every bit of capacity we could. The villagers also showed real public spirit. They knew that if this industry took off, it would mean a lot for Yibin.

In the end, SCATL alone hired more than 10,000 workers, and the local villagers were not even enough to meet its demand. The first-phase project pleased CATL. Over the following years, it increased investment in Yibin, signing agreements from Phase 2 through Phase 10.

In 2022, SCATL achieved an output value of RMB 56 billion (roughly USD 8 billion), accounting for 41% of the total industrial output value above designated size in Yibin’s Sanjiang New Area. Behind the output value is tax revenue, but from the government’s perspective, there are also more intangible social benefits.

Zhou Qiang told us: “SCATL itself now has about 15,000 to 16,000 employees. The broader supporting ecosystem has more than 30,000 people employed across the city. I have studied the ratio of industrial employment above designated size to the urban population in Yibin, and it is about 1:10. There are now over 100 projects in Yibin’s power battery industry starting construction one after another. If fully built, they can create over 80,000 jobs, and the matching urban population could reach several hundred thousand.” Yibin’s permanent resident population has increased by two to three hundred thousand over the past few years, a phenomenon rarely seen in the western regions which typically see a net outflow of population.

CATL did not choose Yibin as charity or poverty alleviation. The most immediate benefit of building a plant here is lower costs. Leaving aside land prices and various preferential policies, electricity alone can save the company a great deal.

Battery plants are major electricity consumers. When I was interviewing in Changzhou, Sun Zhihong, a local industrial policy official, once walked me through the numbers: “If a battery plant uses 500 million kilowatt-hours of electricity a year, and in some parts of Southwest China with abundant hydropower resources, the hydropower price can be 0.20 to 0.30 yuan cheaper per kilowatt-hour than what we pay,” then for the company, a single factory can save more than RMB 100 million in profit each year.

In Sichuan Province, where 80% of electricity comes from hydropower, this advantage is even more pronounced. For example, the Yibin Lingang Economic Development Zone, where SCATL is located, benefits from the national policy for a “hydropower absorption demonstration zone”: electricity costs only RMB 0.35 per kilowatt-hour there, while industrial electricity in a certain city in Jiangsu costs RMB 0.68 per kilowatt-hour.

“SCATL uses tens of billions of kilowatt-hours of electricity a year in Yibin. Let’s calculate based on 2 billion kilowatt-hours: if each kilowatt-hour is more than 0.30 yuan cheaper, that adds up to 600 to 700 million yuan, equivalent to an extra RMB 600 to 700 million in profit,” Zhou Qiang said.

The production process for lithium batteries requires extremely strict environmental controls. Keeping the entire workshop at constant temperature and humidity consumes a great deal of energy, which is also one of the points frequently criticized about the lithium-battery industry. Even though lithium batteries are a core component of the new-energy sector, the high energy consumption brought by their manufacturing processes, combined with the fact that China’s power supply is still dominated by coal-fired generation, creates an environmental contradiction for the industry. This not only troubles the sector on a moral level, but is also a real, practical challenge for industrial development.

Zhou Qiang explained to us: “Domestic lithium-battery products are exported to developed markets in Europe and the United States. They have a non-tariff barrier, what they call a green barrier, where they track your carbon footprint to see whether you meet the standard. You can say your product is green, but if it is produced using thermal power, it is not green. Hydropower counts as green electricity.”

Zeng Yuqun also repeatedly said at the World Power Battery Conference in Yibin in 2023 that CATL aims to achieve carbon neutrality in core operations by 2025, and carbon neutrality across its value chain by 2035.

This means that by 2025, CATL’s battery plants will all be zero-carbon factories, and by 2035, the batteries it produces will all be zero-carbon batteries, achieving carbon neutrality across the entire chain from mineral resources to the battery itself. To reach this goal, whether for CATL’s own plants or its suppliers, the appeal of green electricity becomes hard to ignore. Companies must reduce carbon emissions during production and prioritize clean energy such as hydropower and wind power.

In addition, Yibin, though seemingly tucked away in the southwest, is not behind in transport. Compared with other southwestern cities, it even has advantages. A look at the map shows that Yibin sits right at the intersection of an X-shaped high-speed rail network connecting four major southwestern cities—Chengdu, Chongqing, Kunming, and Guiyang—and any one of them can be reached within two hours.

Yibin is also the first major city along the Yangtze River when counting from its source. Its urban area is built at the confluence of three rivers — the Jinsha River, the Min River, and the Yangtze — giving it an exceptionally dense and well-developed water system.

Zhou Qiang said: “In Jiang’an County under our jurisdiction, there is a battery supply-chain company. The ore it buys overseas can be unloaded directly at Yibin Port, then transferred by road to the factory. Land transport usually costs five or six times as much as water transport, but the distance from Yibin Port to its plant is only a few dozen kilometers. It only needs road transport for that short stretch. If it were elsewhere, transportation costs would be much higher. Right now, we’re considering helping them save that money too by opening another dock in Jiang’an, so that the iron ore can be shipped directly into their factory.”

How an industrial cluster takes shape

Once CATL, as the “chain leader,” moves in, putting the whole Lego set together becomes much easier. The lithium-battery industry has many segments and a long supply chain, so to improve efficiency it naturally tends to concentrate geographically.

Whether in Changzhou in the east or Yibin in the west, once the industry lands, clusters form quickly. Factories spring up one after another, side by side, a phenomenon insiders call “wall-to-wall factories.”

“CATL is huge. It has pull and bargaining power. Put differently, supply-chain companies have to chase after it,” Long Xingyin told us. Long previously oversaw investment at Yibin Emerging Industry Investment Group.

For many places, lithium batteries are a brand-new industry. When CATL builds a new plant somewhere, there are often no local companies, or very few, that can supply it directly. “

That’s why CATL has maintained a long-term ecosystem partnership with the CDH Fund, which mainly invests in CATL’s supply-chain companies. After CATL signed its agreement with Yibin, Yibin Emerging Industry Investment Group partnered with CD Fund and set up a fund dedicated to investing in CATL’s supply-chain companies. The fund moved fast: the first tranche was RMB 3 billion, and it was fully invested in less than two years, bringing dozens of supply-chain companies into Yibin.”

An industrial cluster is an ecosystem. The chain leader can obtain upstream raw materials and components nearby to reduce costs, and can communicate more closely with supporting companies in R&D and manufacturing, inspiring each other and driving further innovation and iteration.

LIBODE, a cathode-material company founded in 2017, was Yibin’s first enterprise related to the lithium-battery industry. It initially struggled to stand on its own, but after the cluster formed, it rose rapidly. Now, within a half-hour drive from LIBODE’s plant, many battery factories can be found.

“The advantage of battery plants is that they deal with many cathode-material companies nationwide. They have seen more, and they hold more information than we do,” said Zhang Bin, LIBODE’s deputy general manager. “This is an industry run by smart people. Someone will always think of what others don’t. Right now, several of our new materials have already been sent to customers for testing. At the same time, we’re also engaging other customers. Different power-battery companies follow different technology routes, so we need to develop cathode materials they may be interested in, as well as materials that can help steer the market.”

Also entering Yibin alongside CATL was Tyeeli (Yibin) Co., Ltd., which produces and sells battery-grade lithium hydroxide. Its chairman, Pei Zhenhua, is a shareholder of CATL, and the two parties also jointly established Tianyi Lithium. For Tyeeli, CATL is both a shareholder and a customer.

Shenzhen Kedali Industry Co., Ltd is a company making precision structural components for lithium batteries and structural parts for automobiles. Its lithium-battery structural parts account for 31% of the global market. It also opened a branch plant in Yibin and became CATL’s largest local supplier of structural parts. Dozens of supply-chain companies like this have landed in Yibin.

Next to Kedali is a company called Liangya New Materials亮雅新材料, founded in 2019 and newly admitted into CATL’s supply chain.

When I arrived at the company, its owner, Luo Wei, was about to head out on a business trip with samples in hand — one piece looked like a thin sponge, the other like a strip of tape. Luo demonstrated on the spot: he took out a lighter and burned the tape. Not only did it fail to ignite, it did not even show scorch marks.

Luo said: “We mainly make functional materials such as insulation, thermal insulation, electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity. For example, news reports sometimes say that after a battery catches fire, car doors and windows cannot be opened. That is because cars now have no mechanical locks, only electronic locks. The high temperature generated the instant the battery burns destroys the circuits. Our material is used inside the battery pack. In temperatures of 1,000°C to 1,400°C, it can hold out for at least five minutes and will not let the wiring burn through.”

Luo has worked in this industry for 20 years. He started out working with Taiwanese partners, then founded his own company in Dongguan 10 years ago and witnessed phones evolve from feature phones to semi-smart phones to smartphones. His customers include major brands such as Apple, OPPO, and VIVO. But in recent years, Dongguan has become intensely competitive, and customers pushed him to set up factories in Southeast Asia. Another option was to follow the phone industry’s shift toward the southwest.

Luo is from Sichuan. There are not many companies like his in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, so he came to Yibin to open a branch plant, and unexpectedly found new gains.

Many of the companies near his plant are in the power-battery supply chain, and information circulates among neighbors. Luo realized that battery plants also need functional materials such as thermal insulation, flame retardancy, and insulation: “The battery pack needs to be wrapped in flame-retardant materials both above and below. Even the screws and screw caps on the water-cooling plate are sealed up.” In the past, most of these materials relied on imports and were expensive. For example, a material called silicone foam cost RMB 300 to 400 per square meter.

Luo spotted an opportunity. He believed these materials were not difficult to make. With research institutes he had long worked with, and after two years of R&D, he developed silicone foam with the same functions, priced at just over RMB 100 per square meter. And that tape that fire could not burn through: “Other companies have a very complex process that takes five steps. We developed a process that only needs two. The procurement price used to be RMB 65 per square meter. Now I sell it for RMB 35.”

Behind such low prices is 20 years of hard-earned market experience in the fiercely competitive 3C industry. Luo said: “Foreign companies and Chinese companies price differently. Take Japan and South Korea. If they develop a material, they might produce 100,000 square meters a month and sell it at RMB 100 to protect their profit margins. They’re relatively conservative in how they estimate the market and use scarcity-style marketing. China has a huge market and pursues volume. Costs come down through scale, and I can still make money selling at RMB 60.

After making the samples, Luo still saw himself as a “small player” who could not reach CATL’s procurement managers. Yibin’s government proposed providing “mom-style service” for companies settling in the park, and the names of the designated liaison staff are even posted at the entrance of each firm. Luo hence found Guan Min, the director of the investment-promotion office responsible for their park. Guan came to the company, made introductions, and successfully helped Luo win the trust of CATL as a major client and reach a cooperation agreement.

After stepping into this new industry, Luo updates his understanding every day. “In Apple’s supply chain there are many small suppliers, but in CATL’s supply chain there are basically none. My earlier understanding was very superficial — I thought the functions were the same. But after working with CATL, I realized that while Apple’s requirements are also very high, it doesn’t really involve safety. A phone can have a black screen or poor signal, but in cars, safety is always the top priority. In the 3C field, testing a function for a week is enough. Now sometimes testing takes months.”

Luo is considering moving his company headquarters from Dongguan to Yibin, because he sees many opportunities here. During the few days he spent in Yibin, he communicated with Kedali next door and found they also need these functional materials. He has already begun producing samples, hoping to close a deal worth tens of millions of yuan.

In Changzhou, I interviewed Hymson Laser Technology Group Co., Ltd., a company focused on laser die-cutting equipment mainly used for cutting and cleaning electrode sheets. Founded in 2008, it previously concentrated on the 3C industry and entered Apple’s supply chain, but in recent years it has shifted its business focus to the lithium-battery industry.

Li Rui, a staff member at Hymson’s Changzhou plant, is in his thirties. He is from Suizhou, Hubei Province. He joined Hymson in 2014 and in 2020 was assigned from the Shenzhen headquarters to Changzhou. He took me on a tour of the plant’s production line. Hymson began R&D on lithium-battery laser equipment in 2015 and started mass production two years later. During that process, it directly transferred much of the technology and experience it had accumulated before. In 2017, Hymson built a plant in Jintan District, began operations in 2019, and subsequently entered the supply chains of many leading manufacturers.

As I reviewed the supply-chain companies I interviewed on this trip, I found that many entered the lithium-battery sector through this kind of “cross-over”: some started in trading, others began in mining or large chemical conglomerates, and quite a few were originally part of Apple’s supply chain. Even if some companies’ previous core businesses were not directly related to batteries, a deeper look shows they could usually connect to the lithium-battery industry in one way or another.

Just as Japan’s Sony once leveraged the foundations of the photographic film industry, China’s rapid lithium-battery development is also a reflection of broader manufacturing capabilities. These companies have found new paths for transformation in the lithium-battery sector, and their “cross-over,” in turn, has brought technical and experiential support that helps raise the level of lithium-battery manufacturing.

The pressure and logic behind local-government investment promotion

From the perspective of local governments, the “clustering” phenomenon in the lithium-battery industry makes it an ideal target for attracting investment, especially after China’s economy entered the “new normal,” when industrial transformation became the top priority faced by virtually every locality. The success or failure of that transformation does not merely affect the promotion prospects of a few officials; it also determines the trajectory of a place’s economic development and the shifting fortunes of its residents’ lives.

Take the ride-hailing drivers we dealt with in Changzhou. Many were from other places. Some used to work in factories. After saving some money, they wanted a different life and bought cars to drive ride-hailing. Others used to run small businesses locally, then the pandemic wiped them out, so they switched to driving to make a living, while waiting for another chance.

Because lithium batteries brought more people in and out of Changzhou, including me, we became their customers and provided them income. Industrial development brings not only high-end technology and chances for factories to start production, but also an overall pull on local employment and the socio-economic fabric. It tends to create opportunities, whether for senior managers or for primary-level service workers.

In terms of motivation to develop new industries, inland Yibin is undoubtedly stronger. Yibin’s longstanding industrial pillars have been wuliangye and coal. While these provide stable revenue, they also face growth bottlenecks.

Zhou Qiang once worked at the municipal finance bureau. He said, “Traditional industries are mature industries, and their growth rate will slow. If we want to maintain high-speed growth, we must open up new space.”

Yibin’s GDP has long been stably ranked fourth in Sichuan Province. By 2016, Nanchong, which ranked behind it, was closing the gap quickly. Long Xingyin said, “At the leadership level, there was a strong sense that something had to be done — one way or another, Yibin had to move up a level. The fifth regional Party Congress set the strategy: rely on traditional competitive industries and develop emerging industries from scratch. At that time, our understanding of what ‘emerging industries’ really looked like was still quite hazy, so in total we set eight directions: rail transit, smart terminals, new materials, new energy vehicles, medical devices, and so on. If four or five of them could break out, that would already be very good.”

At this stage of China’s emerging industries, getting into this “club” requires a ticket. I was curious why several business leaders independently mentioned that Yibin’s investment-promotion team keeps its word.

Zhou Qiang explained: “Our biggest advantage is confidence. In the 1990s, Yibin’s development strategy was to ‘grasp the big and let go of the small,’ focusing on nurturing a few state-owned enterprises, and Wuliangye Group was one of them. So our state-owned capital is strong. Yibin Development Group is the parent company of almost all local state-owned enterprises. Its national credit rating is AAA, which is very high. The support policies we promise can be honoured with capital, so we can deliver on what we say.”

To make this work, Yibin almost turned itself into a venture-capital firm. Starting from top-level design, it launched reforms, broke through the old institutional structure, and set up a number of dedicated working units. Each unit was responsible for its own industry area, pushing forward in parallel, without interfering with the others.

In 2017, Zhou Qiang was seconded to the New Energy Vehicle dedicated unit, and later moved into the even more specialized power-battery industry. “In the traditional system, all industry falls under the Bureau of Industry and Information Technology, but its bandwidth is limited. If we want to develop multiple emerging industries, we need dedicated units.”

These units have now been institutionalized. Zhou Qiang, for example, was placed into a new agency called the Bureau of Economic Cooperation and Emerging Industries. The Power Battery Division I where Zhou Qiang works is responsible for enterprise services, while the Power Battery Division II handles investment-attraction projects.

Zhou Qiang said: “In a traditional system, investment promotion is handled by the investment-promotion bureau, and after the contract is signed, it’s handed over to the economy and information bureau. That can easily create disconnection between departments. Now, from project attraction, to construction, to enterprise cultivation, to industry operation, one bureau takes responsibility all the way through.”

Zhou Qiang speaks quickly, as if pouring everything out at once, barely pausing even for a sip of water. Yet he is well-organized. He can explain Yibin’s advantages and the origins of this large plan, cleanly and sharply, getting straight to the key points. Investment promotion is, in effect, a city’s sales pitch. In a short time, it must make its strengths and sincerity clear. It was obvious Zhou has delivered this pitch many times.

Of course, talking alone is not enough. Zhou told us that in early 2017, the city established an emerging-industry group, a platform capitalized by governmental funds and combined with private capital. It now has 24 industrial funds, covering the power-battery industry, the automobile industry, the photovoltaic industry, and more, with a total size of RMB 31.7 billion. “Compared with big cities, 31.7 billion may not seem large, but for a city the size of Yibin, it is already a very large scale.”

What Long Xingyin did at Yibin Emerging Industry Investment Group is to provide “landing support” for the companies Zhou Qiang and his team targeted, put simply, to invest.

Long Xingyin originally studied automation and knew nothing about finance when he took on the assignment. He got up at 6 a.m. every day to study fund qualification materials, securities qualifications, company law, insurance law, and the operation of state-owned capital, and he also passed the fund practitioner qualification exam. He said that when he went to Chengdu for the exam, most people in the same room were university students — only he was already in his forties.

Attracting talent, a small city’s challenge

Many local governments hope to attract high-tech industries through preferential policies on land and funding. Changzhou and Yibin have been able to move ahead partly because they also look for ways to attract talent. The lithium-battery industry is a typical technology-intensive sector with strong demand for technical and innovation talent, precisely the weak spot for western cities like Yibin.

Zhou Qiang said: “It is relatively hard for a fourth-tier city like ours to attract talent. Local people go to big cities to study, and it takes real determination to come back. Students from other places who study in big cities are even less likely to come to Yibin to work.”

So while building factories, Yibin also rushed to build schools. The city designated 36 square kilometres at once to build a university town and a science-and-innovation town, attracting 10 universities to set up branch campuses. Walking in the park, I only had to look up to see rows of neatly arranged road signs — each bearing the name of a university. These branch campuses have all been built and moved in within the past three years.

“We call this a ‘turnkey project.’ Teaching buildings, dormitories, laboratories and even desks, chairs, and air-conditioning, we’ve equipped everything. We know that where a person go to university becomes their second hometown. Now we also have industry here, so students who study here are more likely to stay,” Zhou Qiang said.

Yibin is not content with being merely a production base. In recent years, it has also invested heavily in attracting top-tier research talent.

The most emblematic example is its recruitment of Minggao Ouyang, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and a professor at Tsinghua University. In 2020, he placed his only Academician Workstation in Yibin. Starting in 2007, Ouyang has served as the chief expert for the national key science and technology programme on new energy vehicles for three consecutive Five-Year Plans. Dozens of the PhD students he trained are now active across every segment of the new-energy vehicle industry chain.

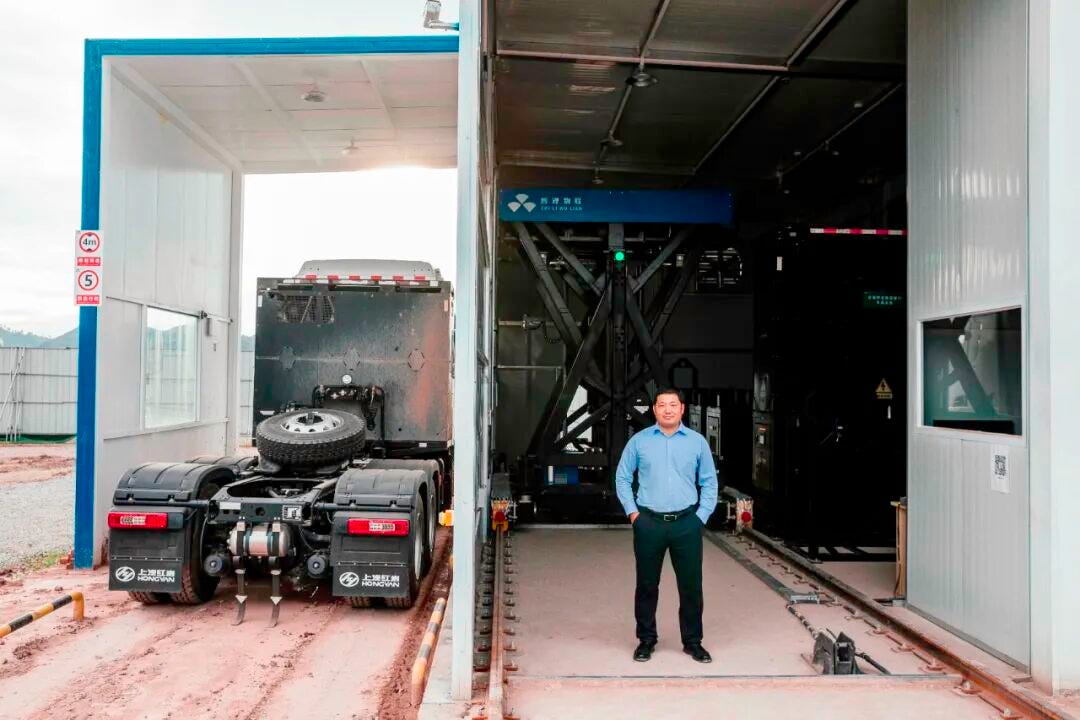

On the day I visited the academician workstation, it happened to coincide with the completion and commissioning of the Zhili IoT factory for a heavy-duty truck battery-swapping project. Heavy trucks account for a high share of carbon emissions in the transport sector. If they can be electrified, the emissions-reduction impact is substantial. Li Liguo, founder of Zhili IoT, is Ouyang Minggao’s student and also secretary-general of the China Electric Heavy Truck Battery Swapping Industry Promotion Alliance.

Yibin put a lot of thought into bringing in Ouyang Minggao. With only one academician workstation, the decision of where to place it required careful consideration. “Yibin’s leaders may have come to visit every year, talking about Yibin’s determination to transform and its natural conditions. In this process, we gradually saw an opportunity for cooperation,” Li Liguo said. “At that time, equipment in our power-battery safety laboratory at Tsinghua University was already packed tightly. Battery testing carries certain risks, and Beijing’s environment also restricts some experiments. In addition, we were beginning frontier research on battery mechanisms. Some equipment can cost tens of millions of yuan per unit. It is possible to secure research funding by applying for projects, but the time cost is high. Yibin not only provided us with excellent office and R&D space, it also funded the purchase of equipment we wanted.”

Although Yibin entered the field relatively late, it has already hosted a high-profile World Power Battery Conference for two years. This is inseparable from the industry’s network support. The unveiling ceremony for Li Liguo’s heavy-truck battery-swapping project was also attended by important experts and entrepreneurs from the sector. Previously, coastal cities in the east had also invited Li Liguo, offering an RMB 8 million subsidy, but he ultimately came to Yibin.

“After Academician Ouyang began working with Yibin, several of us came too, working diligently to build teams here. After our lab was established, our PhD students did research here and gradually got to know the city. This year, three or four postdocs may stay to work here,” Li Liguo said.

“Yibin has not attracted many Tsinghua alumni through the market alone, but the academician workstation brought more than a dozen alumni.” He added that their team is also pushing research results to land in Yibin, sometimes by incubating start-ups, sometimes by cooperating with local companies. “One of our PhDs is doing anode-material research in Yibin. We think his project has industrial value, so we discussed whether he could start a business. After landing, that PhD became the company’s founder.”

This is so good. It's the deep dive narrative into what I can sense intuitively, but don't have the chops to nail it. Americans think it's just commies subsidizing stuff. Nope. Competence, adaptability, resilience, persistence. Beautiful. 美丽

Thanks much.