Current food delivery model in China unsustainable, analysis says

plus a study on the real life of delivery riders by Nankai University

No other country has seen the app-based food delivery industry evolve as rapidly as China.

Born of fast urbanization and digitization over the past decade, this new line of work has brought extraordinary, sometimes unbelievable, convenience to everyday life, while constantly testing long-held social norms and institutions.

For many delivery riders, the job is inherently temporary and in-between. Anthropologist Xiang Biao has likened their lives to "hovering hummingbirds," always in motion yet never settling. Sun Ping, an associate professor at the University of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, calls courier work a form of "transitional labor."

While riders depend on the platform economy for their livelihoods, they also find themselves trapped by the very system that sustains them. You may recall the widely shared essay on China’s internet, "Delivery Workers, Trapped in the System外卖骑手,困在系统里," which captured this tension with rare clarity.

Now, the once unstoppable system is starting to show signs of fragility, according to a recent brief from a Chinese private think-tank.

ANBOUND, founded in 1993 and saying it has served the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Affairs since 1998, says in its latest analysis:

A close look at the food-delivery sector's fundamentals, cost base, and labor structure suggests the industry may soon come off its peak and start trending downward.

It even puts a timeline on it:

under today's delivery model, the industry has roughly a decade of life left.

Demographics top the list:

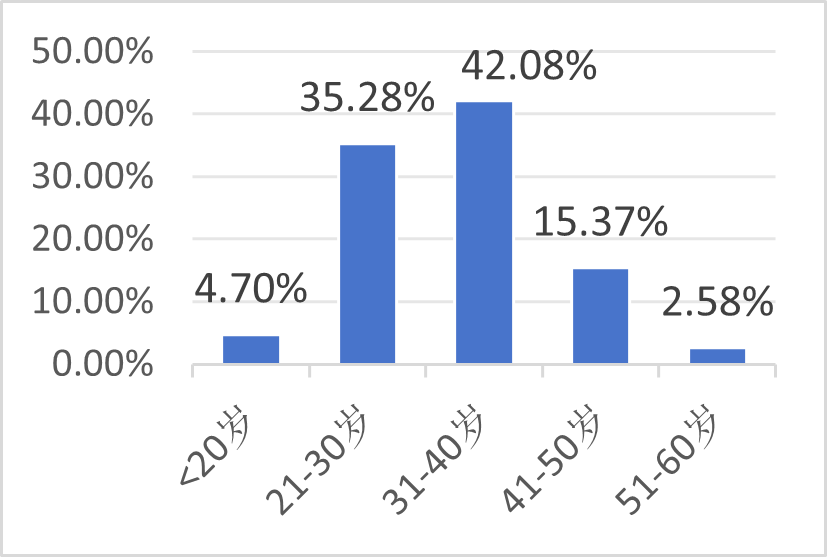

Nearly 80% of riders are between 21 and 40, which is because the work demands exceptional physical fitness… Once past 40, most struggle to keep up with today's intensity… With births declining year by year, and fewer young people willing to take on high-risk, physically demanding jobs, the future supply of riders will tighten structurally.

Climate will also be a major variable:

By around 2035, many parts of China are expected to see summer heat regularly topping 40°C, with heavier rains and more frequent typhoons in some regions. That will sharply raise the bar for high-intensity outdoor work. The safety risks and health burdens of extreme weather will further deter current workers. This is an irreversible, badly underestimated structural challenge, and a material threat to a delivery model that relies on large numbers of outdoor riders.

Finally, costs are rising:

By one estimate, China's food-delivery Gross Merchandise Volume (GMV) reached 1.6 trillion yuan in 2024, with total rider costs at roughly 80–100 billion yuan (10%–15%). The average order value is 50–65 yuan nationwide, while rider cost per order runs 7–9 yuan (14%–18%). Notably, since 2025, localities have been moving to include riders in the social-insurance system. Even without a full employee model, platforms are commonly paying part of these contributions for core riders, adding 0.3–0.5 yuan per order. If coverage expands to full social insurance, commercial insurance, and even housing provident funds, unit labor costs will rise again. Should delivery-service costs climb to 40% of the order price, the model would become unsustainable and tip toward collapse.

The analysis goes further:

By around 2030, rider costs could rise to 40%–60% of an order's value. In practical terms, a 30-yuan meal today would have to be priced at 45–50+ yuan just to preserve platform unit economics. That's an "invisible premium": customers aren't getting more food or better service, they're simply paying the basic logistics needed to keep the platform running. If prices keep climbing without a corresponding lift in perceived value, consumers are likely to shift to other ways of spending.

Looking ahead, the analysis sketches two paths:

A revival of street-level commerce. Retail and dining move back to the "front stage," at least in part. As delivery loses its cost advantage, more consumers will simply head downstairs for meals, creating fresh room for convenience shops, neighborhood storefronts, and street businesses to grow again.

…

Technology substitution — think drones and delivery robots. While technically promising, real-world rollout faces massive systems hurdles: traffic governance, infrastructure, regulation, logistics reallocation, and energy planning. In the next decade, these models will likely be confined to limited pilots in campus-style parks or gated communities and won't support an industry-wide transition.

Between the two, a comeback of street commerce looks more plausible.

Additionally, in December 2024, a research team from the School of Social Sciences at Nankai University published the "A Study on the Real Life of Delivery Riders 外卖骑手的生活世界研究," based on 41,000 sample data. The report outlines the profile of delivery riders, their family strategies and life characteristics, as well as the key factors influencing their quality of life.

This report was released on their official WeChat public account, and I have translated it into English as follows.

If this profession is indeed on a path to decline in the coming decades, I hope the lives of riders and their contributions won't be forgotten so quickly.

外卖骑手的生活状况及其质量提升——外卖骑手的生活世界研究

Living Conditions of Delivery Riders and Quality Improvement: A Study on the Real Life of Delivery Riders

Starting from riders' "lifeworld" and using it as the main lens on their circumstances, this study surveyed 41,893 delivery riders through questionnaires, participant observation, fieldwork, and semi-structured interviews.

It seeks to answer: How do riders present themselves in their lifeworld? What are the traits of that lifeworld? What factors shape riders' quality of life? And how can that quality of life be improved?

Concretely, we outline riders' daily routines and work arrangements and their social ties to sketch a "life portrait," then probe the generative logic and content of their main life features. From a wider perspective, by examining the work and life worlds in which riders act, we glimpse how deeper economic, social, and cultural structures affect their lives, and how riders' living conditions, in turn, shape their work.

Portrait of delivery riders

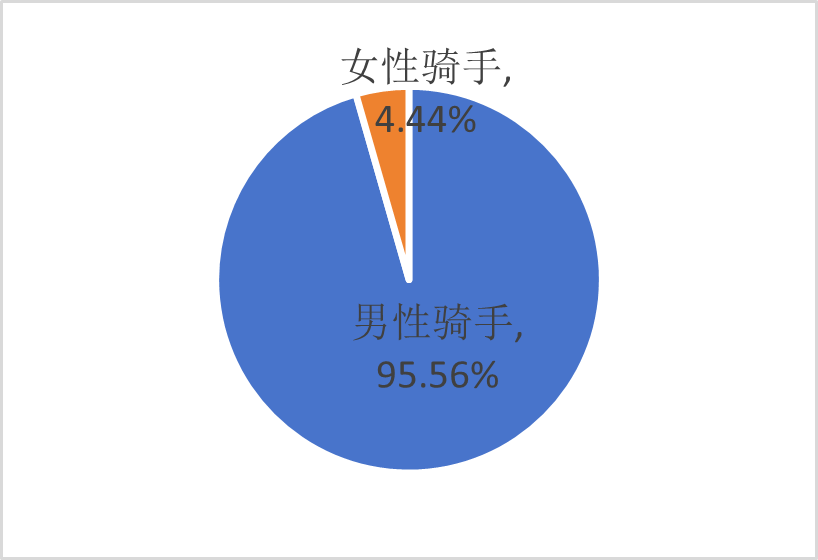

Most riders are male and in their prime working years, better able to meet the physical demands of the job. Men account for 95.56% of riders, while women make up 4.44% (see figure 1). The average age is about 33. Nearly 80% are between 21 and 40: riders aged 31–40 account for 42.08%, and those 21–30 for 35.28%. In addition, 15.37% are 41–50, 4.70% are under 20, and 2.58% are 51–60 (see figure 2).

Because entry barriers are low, the sector offers relatively stable jobs to large numbers of workers with modest formal skills. Delivery work provides a relatively flexible environment and, compared with many other industries, more attractive earnings, helping riders ease pressures such as loan repayments.

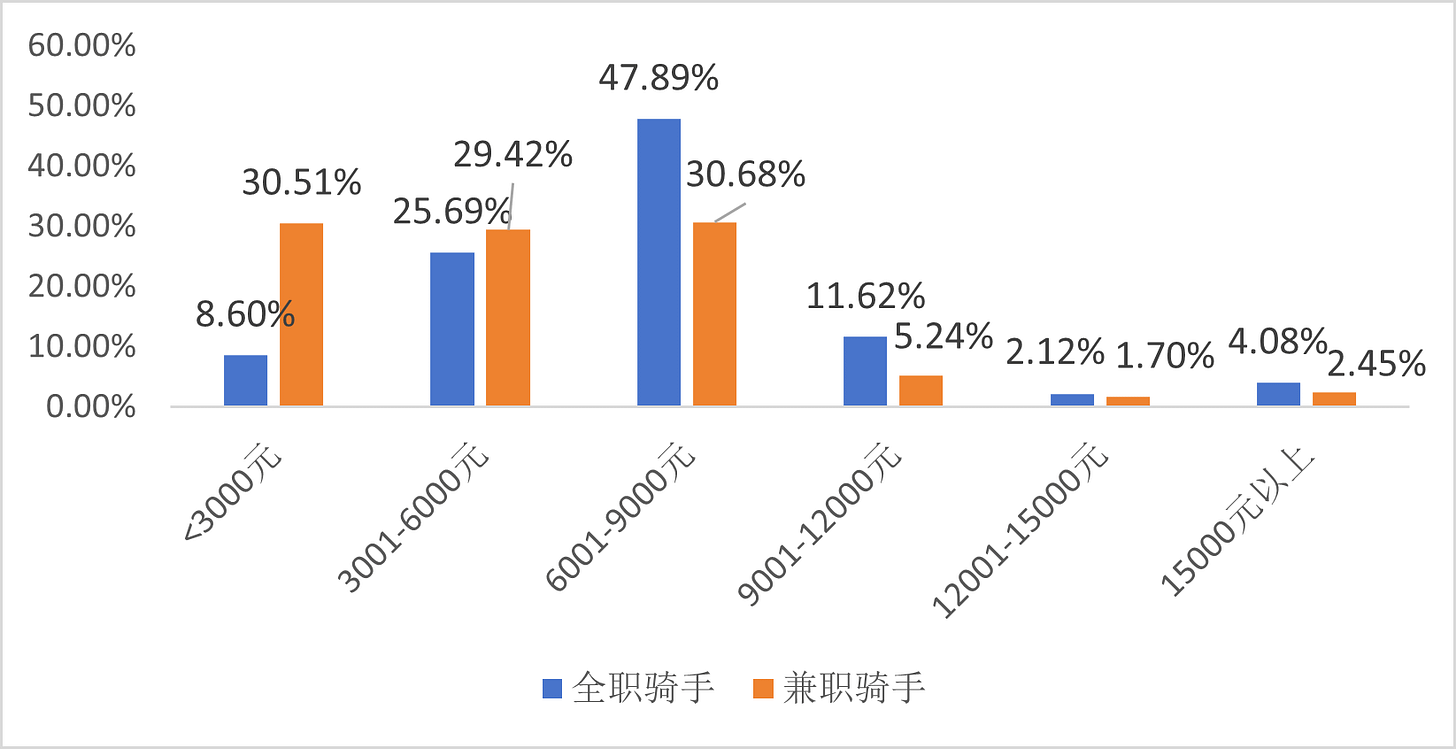

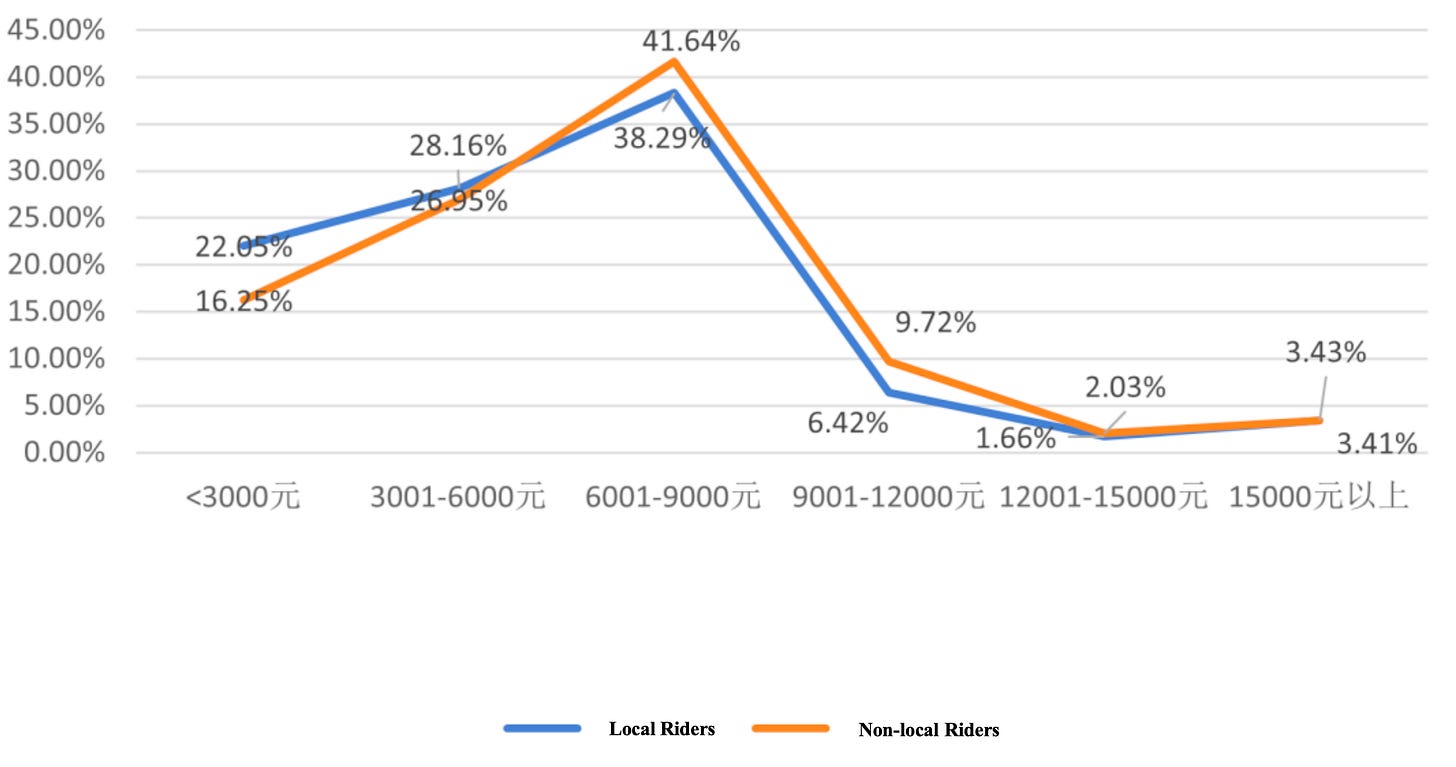

"Freedom" is a central reason riders choose this line of work. Nearly every rider mentioned the sense of freedom that comes from flexible scheduling. Before becoming riders, many worked in manufacturing, food and beverage, transportation, or construction. Taking monthly average wages for production-related workers as an example, in 2023 the average monthly wage in manufacturing, accommodation and catering, transportation, and construction was 6,193 yuan, 4,085 yuan, 7,491 yuan, and 5,573 yuan, respectively. By contrast, riders' monthly earnings cluster mainly in the 6,001–9,000 yuan range, and 17.82% of full-time riders earn more than 9,000 yuan per month, suggesting delivery work can pay more than their prior sectors.

Looking more closely, among full-time riders nearly half earn 6,001–9,000 yuan per month, while 34.29% earn under 6,000 yuan. Among part-time riders, the shares earning under 3,000 yuan, 3,001–6,000 yuan, and 6,001–9,000 yuan are roughly balanced at around 30% each. Notably, both part-time and full-time groups include top-earning riders whose monthly income exceeds 10,000 yuan; a meaningful share earn over 15,000 yuan (see figure 3).

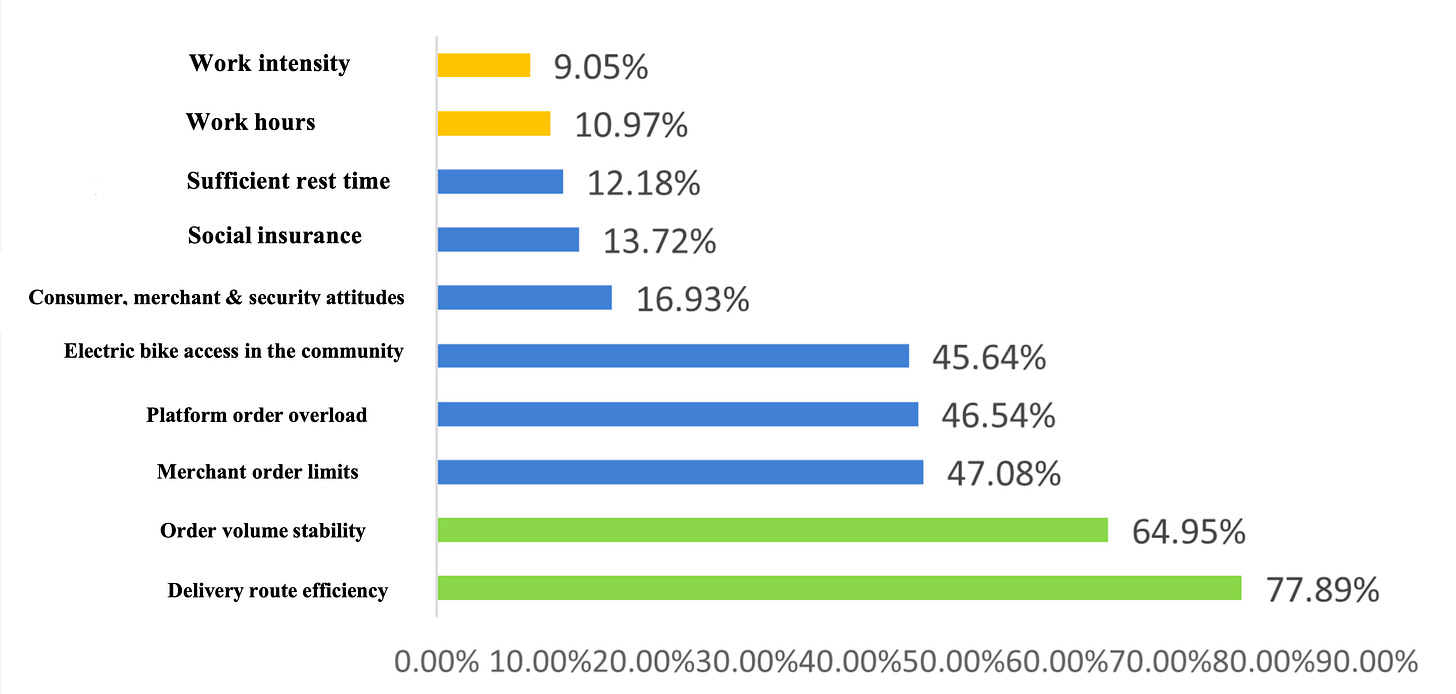

Enabled by digital technology, riders can "see" their work on mobile devices as the labor process and evaluation systems become more open and transparent. Tiered pay systems also enhance riders' sense of participation and reward. Given relatively high debt burdens, riders focus most on income per unit of time. Their top concerns are whether orders are efficiently routed and whether order volumes are stable; they are least concerned about work intensity and total hours (see figure 4). In short, both their work and leisure revolve around "how to maximize earnings," and riders display strong personal agency in scheduling time and rest.

Household strategies

Local and non-local riders differ markedly in family composition and finances, as well as family roles and interaction patterns.

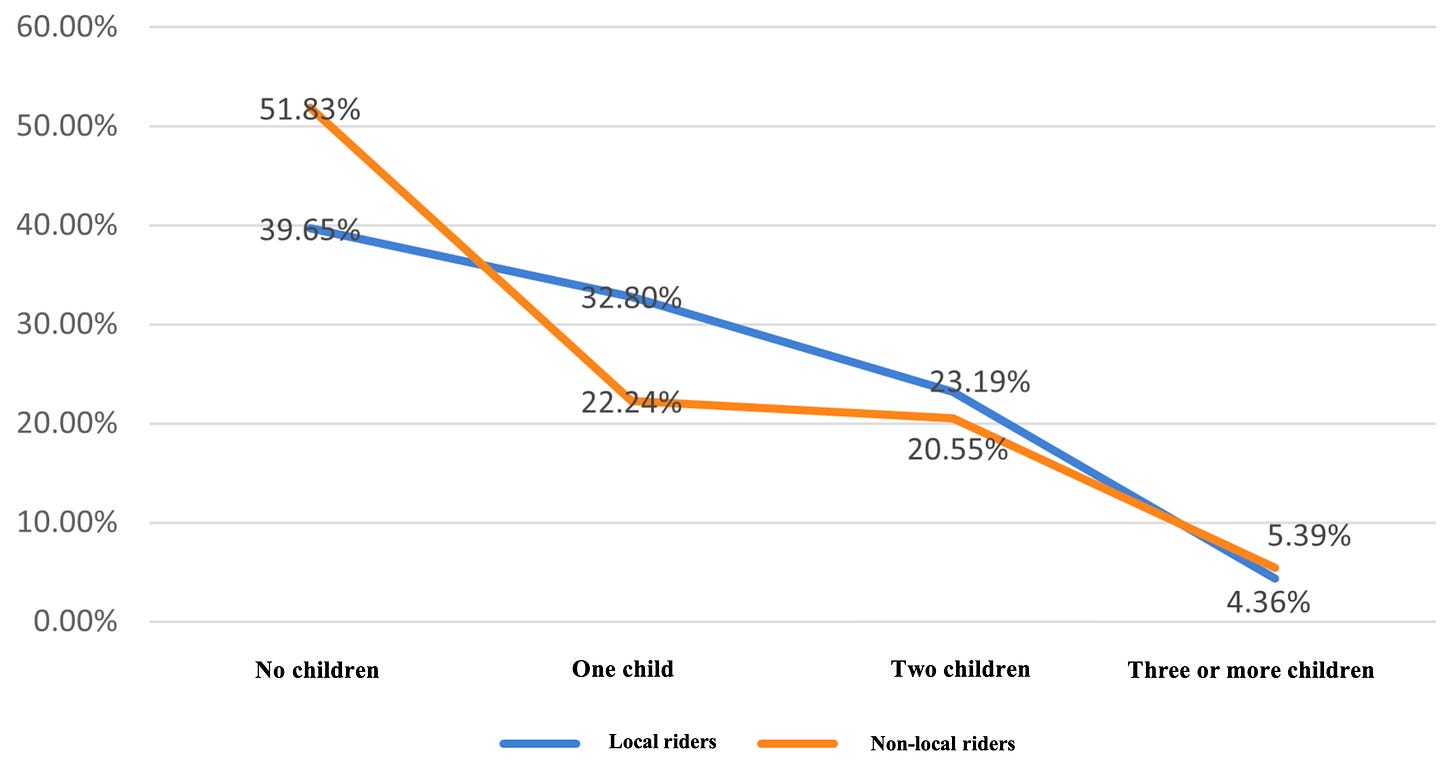

Family composition: Local riders are more often married and more likely to have children, implying heavier family responsibilities. Among locals, 54.4% are married, compared with 43.4% of non-locals. Over half of non-local riders have no children, whereas more than 60% of local riders do (see figure 5).

Economic conditions: Local riders face slightly greater household financial pressure and, overall, have lower incomes than non-locals. A higher share of locals devote over 40% of household income to monthly debt service. On income, 22.05% of locals earn under 3,000 yuan per month, versus 16.25% of non-locals; the shares earning 6,001–9,000 yuan and 9,001–12,000 yuan are higher among non-locals (see figure 6). Even so, both groups include high-earning riders in similar proportions.

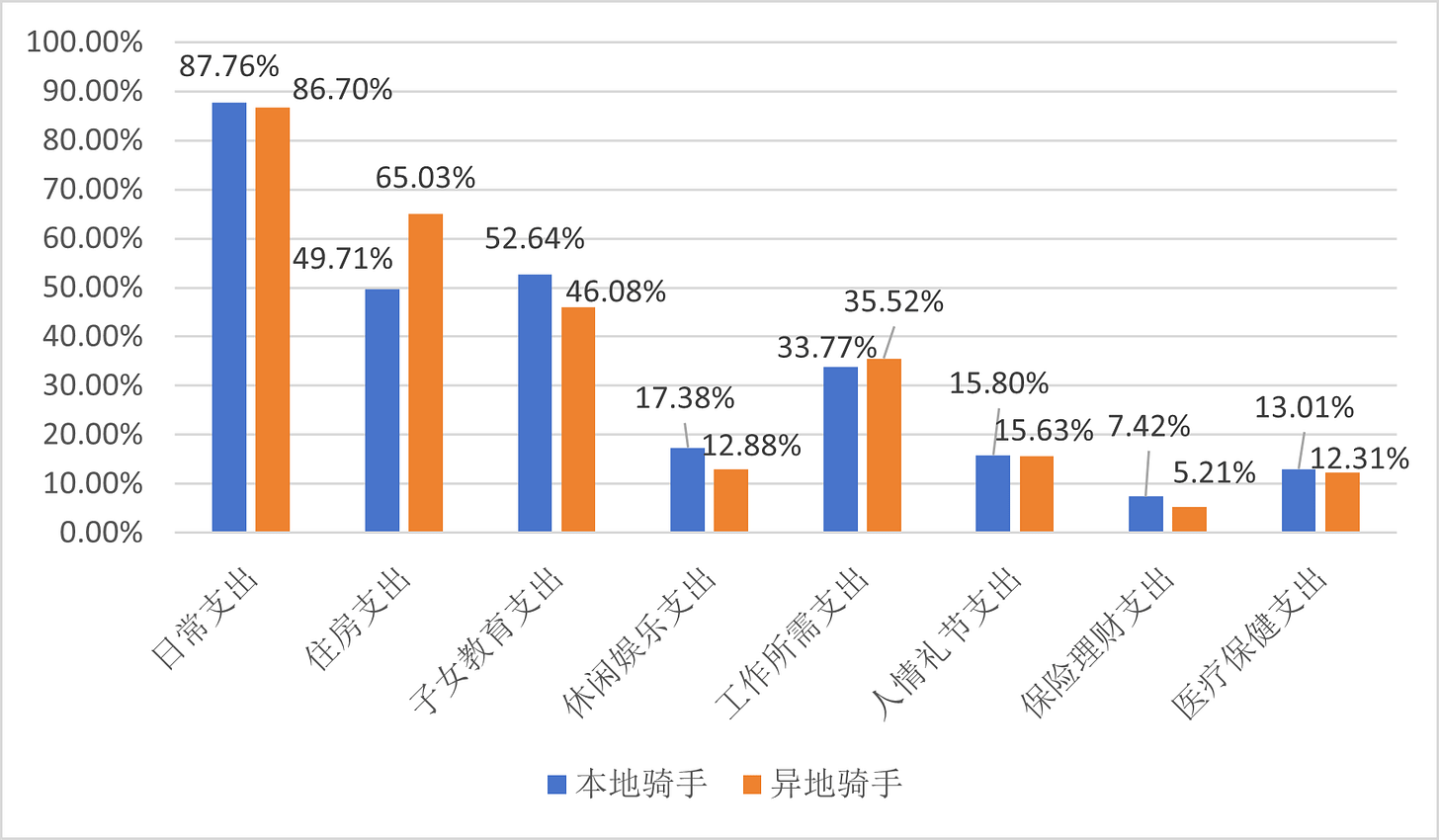

Household spending: The top three categories are daily expenses, housing, and children's education. Housing takes a significantly larger share for non-locals (see figure 7), largely due to rent (72.35% of non-locals rent), while locals more often live in owner-occupied homes (62.59%). Non-locals spend less on children's education and leisure than locals; other categories are similar.

"Sandwich structure": features of riders' lives

Shaped by macro social structures, meso-level industry traits, and micro-level individual factors, riders' daily lives show a "sandwich" pattern: their circumstances are often caught between two poles and influenced by both.

I. Amphibious urban–rural mobility

About 73.93% of riders hold rural household registration, and roughly 79.76% move across regions (across counties, cities, or provinces). They are a classic migrant population: many move from villages to cities as farmers-turned-workers, participating in modern urban labor division. Their daily lives are therefore shaped by both rural habits and urban lifestyles.

II. Pillars juggling eldercare and childcare

Delivery is labor-intensive and male-dominated: 95.56% of riders are men, and 92.72% are aged 20–50. Many thus live the "middle" life of supporting parents while raising children and serve as the family's backbone — guiding direction, bringing in resources, and coordinating affairs. Notably, this family structure and its developmental needs are key to riders' strong job performance.

III. Busy lives that blur online and offline

Because scheduling is flexible, riders have autonomy over when and where to work and when to log off. Boundaries between "work" and "life" are fluid. In short breaks, riders carve out micro-moments — listening to music, scrolling short videos, reading novels — to step out of the work mood for enjoyment or self-satisfaction. Even within limited time, they proactively choose activities that ease body and mind and improve efficiency, which is another facet of their busy state.

IV. Transitional careers

Studies show average tenure is under 12 months, and 24.7% have left the sector at least once after entering it (Zheng Guanghuai research team, 2020). High occupational mobility is a defining feature. For many, delivery is a transitional job, a buffer after failed ventures or unsatisfying positions, and a springboard to the next role, including a way to save capital for future moves.

V. Pulled forward, pushed from behind

All jobs impose constraints, and riders recognize this. But they emphasize the benefits, especially income security. Their drive reflects both attraction (comparative advantages of delivery work) and pressure (failed entrepreneurship, family debt, daily expenses). After weighing their abilities and family situation, many prioritize riding among feasible options; daily rhythms are shaped by platform incentives and life pressures.

Key factors affecting riders' quality of life

Riders' living conditions directly reflect their quality of life, which in turn is shaped by multiple factors: individual, enterprise, social and institutional.

I. Individual factors

• Personal capability: Stronger comprehensive ability correlates with higher quality of life.

• Life attitude: More open and positive attitudes align with better outcomes; negative or extreme attitudes with worse ones.

• Life experience: Past experiences provide premises and reference points that closely relate to current quality of life.

• Life concepts: Differences in consumption, leisure, socializing, and diet shape lifestyle types; healthier concepts support higher-quality living.

II. Family factors

Family structure: As a core part of riders' lifeworld, family structure significantly affects quality of life, including how attention is allocated across life domains.

Household finances: Better household financial conditions generally support higher quality of life.

III. Enterprise factors

Firms use piece-rate pay with tiered compensation and reward-and-penalty mechanisms. Being transparent and predictable, these systems provide foreseeable income streams, allowing riders to choose whether to work very hard, moderately, or minimally.

IV. Institutional factors

Riders who actively join community life and integrate into their surroundings tend to receive better feedback. Successful social integration enriches life experiences and supports higher quality of life.

Discussions on improving riders' quality of life

Riders' lifeworld has its own occupational features and impact pathways. Focusing on quality-of-life improvements and drawing on the above analysis, this research offers several reflections on riders' all-round development.

The "working world" and the "life world" of riders each have their own logic, yet they are tightly linked. Material production and income from work underpin the life world, while rest and mental nourishment in the life world enable better production. The relationship is mutually reinforcing. Negative emotions generated at work can spill into life, affecting choices and quality of life; conversely, personal arrangements and family coordination can facilitate higher work efficiency.

Shifting the vantage point from work to life, truly enhancing riders' sense of reward on the job and happiness at home requires listening to their real voices and addressing the practical issues they care about. Riders' main aspirations for a better life center on income, safety and security, career development, and children’s education—spanning basic survival, safety, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. Meeting such multi-level needs calls for the participation of multiple actors and targeted solutions to different rights-protection issues.

Very interesting .. India too is seeing a boom in food delivery business. Analysts say -

Scale gap: China’s food-delivery GMV (~USD 220B) is nearly 10× India’s (~USD 26B).

• Order value gap: Average order in India is about half to one-third the value of a Chinese order.

• Cost share: Rider cost as % of order is slightly lower in India (~10–12%) vs China (14–18%).