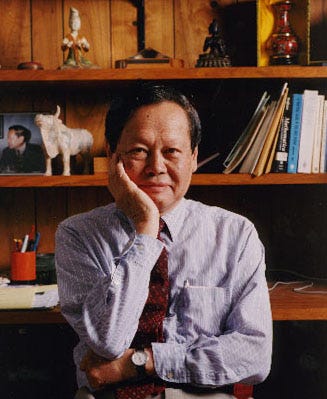

Chen-Ning Yang on China's brain drain and China-US talent exchanges

a mindset with care, balance and restraint that is much-needed to navigate today's bilateral ties.

Chen-Ning Yang, a Nobel Prize winner often ranked alongside Albert Einstein as the world's greatest physicists, died in Beijing on October 18, 2025, at the age of 103 after an illness.

His life, moving back and forth across the Pacific, was a vivid mirror of China-U.S. exchange. As he said at the Nobel Banquet in Stockholm 50 years ago:

As I stand here today and tell you about these, I am heavy with an awareness of the fact that I am in more than one sense a product of both the Chinese and Western cultures, in harmony and in conflict.

Amid today's fraught politics, when talent exchange is constrained or even stalled and national security is too often overemphasized, it is worth revisiting Yang's 2001 Q&A at Peking University.

On questions on talent exchanges, such as whether Chinese students should study in the U.S., whether to return, and how the two student groups differ, Yang answered with care, balance and restraint by encouraging two-way exchange while speaking frankly about each country's strengths and weaknesses, a clear-eyed mindset needed to navigate today's bilateral ties.

The video of that talk has circulated widely in China. My English translation follows below.

May Professor Yang rest in peace.

Question

I'd like to ask three questions today. My first question relates to what you just said about the importance of talent for a country, and that China has many talented people. But there's a problem that really troubles us here at Peking University: a large share of our students go abroad, often in waves, yet when they return, it's one by one.

So my first question is, should Chinese students go abroad? And if they do, should they come back?

My second question is, you once said Chinese students are relatively weak in hands-on experimental skills. Could you offer some advice, both for universities and for students, on how to strengthen experimental training? What should schools do, and what should we as students work on ourselves?

My third question is, when you compare Chinese and American students, what do you see as the strengths and weaknesses of each?

Yang's answer

Thank you. Let me take these one at a time, all right?

On the first question — whether we should encourage young people to go abroad, and whether we should encourage them to return — this is complicated. Ask different professors and you'll hear different answers; both sides have their reasons. I can only share my own view.

First, students should understand that undergraduate education at institutions like Peking University, Tsinghua University, and Shanghai Jiao Tong University is not inferior to the very best schools overseas; one could even say in some respects it is better. Many people don't fully appreciate this.

As for doing research, the environment at China's top universities may lag the very best American schools somewhat, but compared with second- or third-tier U.S. universities, it is not necessarily worse. Many students aren't aware of that.

That said, if an exceptionally good student wins, say, a scholarship to Stanford, and you ask whether I support that student going abroad — yes, I do. The opportunities there may well exceed what's available at home, and the student may grow into outstanding talent. Of course you could say that if they remain overseas it's a loss for China — we invested so much only to "send one more to America." There's truth in that.

But look at what's happening today: why are so many high-achieving young people returning China? Because of Deng Xiaoping's reform and opening-up policy. Deng foresaw that twenty years later these people would have a major impact on China's development and education. It's a complex issue, and as China's economy keeps improving, its ability to attract these talents back grows.

Take Taiwan as an example. Many who left Taiwan in the 1950s did not return then, but in the 1980s, and especially the 1990s, many did. A great number of those who drove Taiwan's economic take-off were precisely people who had gone out, built up experience, and then were brought back. From a long-term perspective, letting our very best go to the world's top universities so they can fully develop is, in my view, a wise policy.

As for returning to China, that's a decision each person must make based on family background, personal goals, field of study, and domestic conditions. In the 1940s and 1950s, the two most famous young Chinese mathematicians, Hua Luogeng and Shiing-Shen Chern, made opposite choices.

I knew both very well. Mr. Hua returned in 1950, founded what became the Chinese school of mathematics, and trained many students. I think in his later years he felt it was a profoundly right decision. Mr. Chern, by contrast, stayed in the United States and made monumental contributions, steering differential geometry in a new direction. In the 1930s and 1940s the field was at a low ebb; he inherited ideas from his teacher Élie Cartan and developed them into what became known as global differential geometry, which later turned into a hot area. At that time, American differential geometry had little standing; after his work, the United States came to lead the field.

Perhaps you know this, perhaps not: Mr. Chern has since returned to China. He is ninety this year, has long resided at Nankai University, founded a mathematics institute there, and has had a decisive influence on the development of young Chinese mathematicians.

People's circumstances differ. On a question this complex, there can be no single answer. But our experience shows there are different paths — through different forms one can contribute to the future of the Chinese nation.

Your second question seems to be the comparison between Chinese and American students. There is a sharp contrast because customs, habits, and traditions differ. I often say one can put China's educational philosophy at one pole and America's at the other; Europe lies somewhere in between but closer to the U.S., while Japan and Korea are closer to China.

The core difference is this: American education places great emphasis on inspiration and inquiry; China's emphasizes step-by-step, systematic learning. You can see it immediately if you watch Chinese and American students side by side at a U.S. university. When I arrived at the University of Chicago in early 1946, I grasped this within a week or two.

Which is better? It's complicated. China's approach has significant advantages: students build up layer by layer, so the foundation is solid.

When Chinese students come to the U.S. and sit next to American classmates, the Americans often appear to know a very broad range of "upper-level" material, because inquiry-driven education gives them many channels to new information. But the downside is many gaps. The result is that in quizzes and exams — mostly theoretical — Chinese students often outperform their American peers.

Does that prove China's approach is best? Not necessarily. It has strengths and weaknesses. Chinese students tend to be more cautious; they believe the most important knowledge comes from books, because that's how they were trained, and so they're less willing to take leaps. So it's hard to say one model is simply superior.

My own sense is this: before we debate the issue, be clear about whom we're talking about. The conclusion you reach for one student may not hold for another. For any given student, these two approaches produce different outcomes. So start from the student's actual situation — build on what they already do well and make up for what they lack. Broadly speaking, the Chinese model works better for most students. But for exceptionally gifted young people, the American system has its advantages: they may show gaps early on, yet over time they usually find ways to close them.

Many of my well-known friends fit this pattern. Take Murray Gell-Mann. Fresh from his Ph.D. at MIT, he came to Princeton as a postdoc when I knew him. He learned quickly and broadly, yet he had many gaps. Because he was extraordinarily intelligent, he filled them over time, sometimes consciously, sometimes without realizing it. And because he could make big intellectual leaps, he achieved results very early. For someone like him, the American educational philosophy clearly played to his strengths.

But I've also seen some American students who, after a couple of exams, grew anxious. They had assumed that, as first or second in their small schools, they would do just as well — only to find it wasn’t so, because their foundations were weak. I've witnessed tragic outcomes: some dropped out, and some suffered nervous breakdowns or other mental strain.

So this is a very important question, and I don't think there's a single, definitive answer.

As for the third question, how can Chinese students strengthen hands-on experimental ability? Closely related to what we've discussed, let me stress one point. Decades ago, among Chinese studying overseas, as well as their non-Chinese peers and professors, there was a common impression that Chinese were suited to theory but not to experimental work. Why? Largely because students trained in China had little exposure to laboratories and, frankly, very limited experience working with their hands.

American students, from an early age, tinker with their mopeds and later their cars, so they grow very familiar with practical work. In China, such opportunities were scarce in the past and remain relatively limited even today. Against that backdrop, and because Chinese schooling is exceptionally rigorous, Chinese students often do very well on U.S. exams, which are mostly theoretical. This, in turn, has fostered the impression that Chinese are not good at hands-on work.

Are the Chinese really poor at hands-on work? Some people are — I'm an example: I tried and eventually backed off. But many are excellent. Consider the U.S. National Academy of Sciences: it has about 2,000 members, roughly a tenth, around 200, are physicists. By my rough count, some 20 are of Chinese origin, and the vast majority — perhaps 80 percent — are experimentalists. Many of them went abroad intending to do theory. Samuel C. C. Ting, for instance, has said that when he went to Michigan he planned to study theory — he had a very strong grounding in Taiwan. But when he met George Uhlenbeck, he was told that physics, at its core, is experimental. He switched to experiment and, of course, produced first-rate work.

These examples show that Chinese are perfectly capable of hands-on work. The notion that we are not is a misconception. With that in mind, I hope the many young people here will recognize this: given the right conditions, Chinese are no less adept at practical, hands-on work than anyone else — indeed, one might even say, in some cases, more so.