Anti-involution vs. supply-side structural reform: What's different?

different macroeconomic environments, industry sectors, causes, and paths of implementation.

Ten years after China introduced supply-side structural reform in 2015, the country is once again facing the challenge of eliminating excess capacity, known as "anti-involution."

I recently wrote a newsletter compiling the insights from top economists advising Beijing on overcapacity. I'm happy to share that it has resonated with many readers. If you haven't had a chance to read it yet, I highly recommend checking it out!

Many view this new round of "anti-involution" as a repeat of the 2015 supply-side reform, which primarily focused on five key tasks: cutting overcapacity, reducing excess inventory, deleveraging, lowering costs, and strengthening areas of weakness. Upon closer inspection, however, the two reform periods differ in several aspects, including the macroeconomic context, industry scope, underlying causes, and strategies for addressing them.

In a recent report, Luo Zhiheng罗志恒, Chief Economist and Head of Research at Yuekai Securities, and Senior Macro Analyst Huang Yu黄羽 explore the similarities and differences between this new wave of reform and the 2015 supply-side initiative.

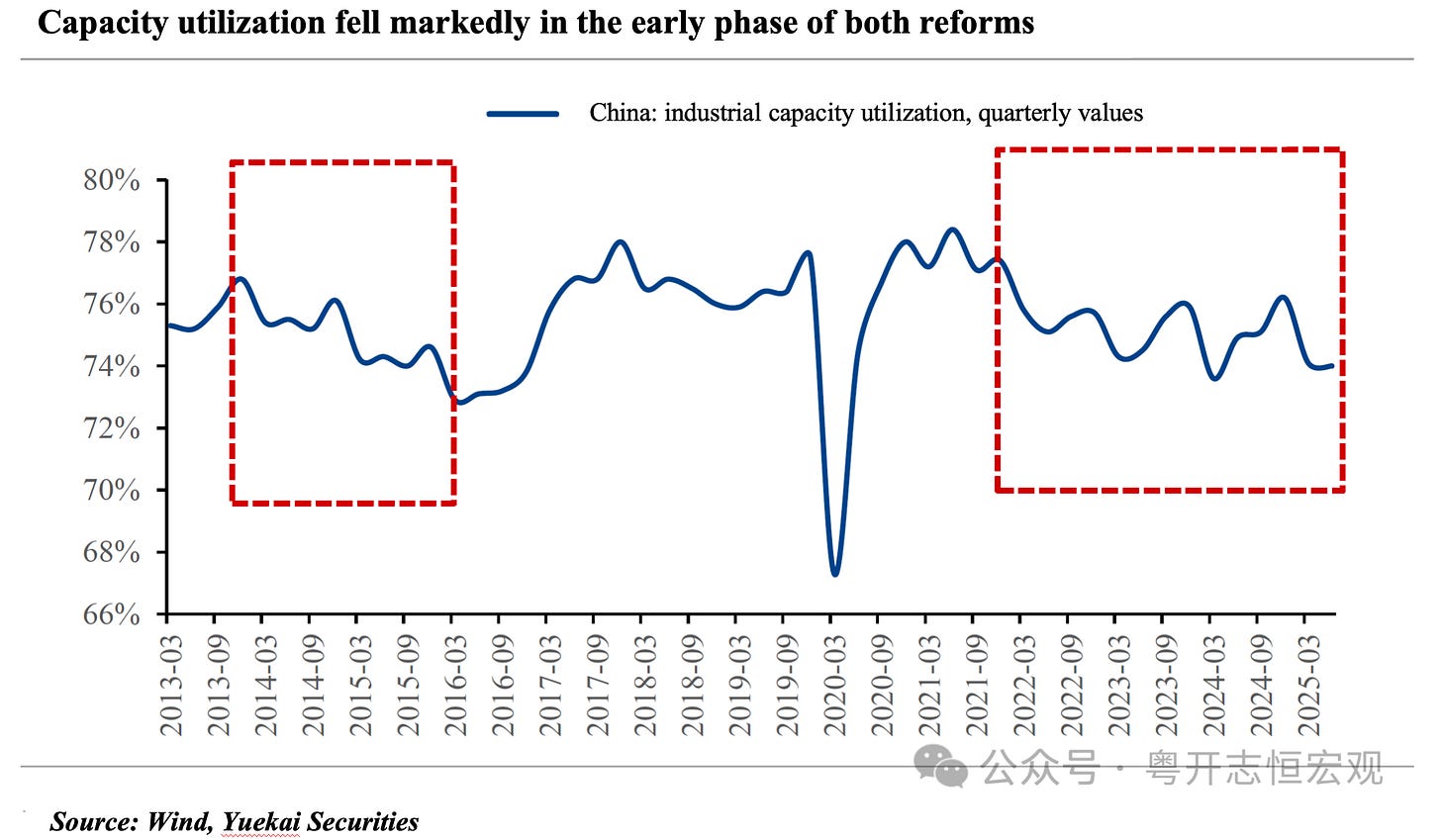

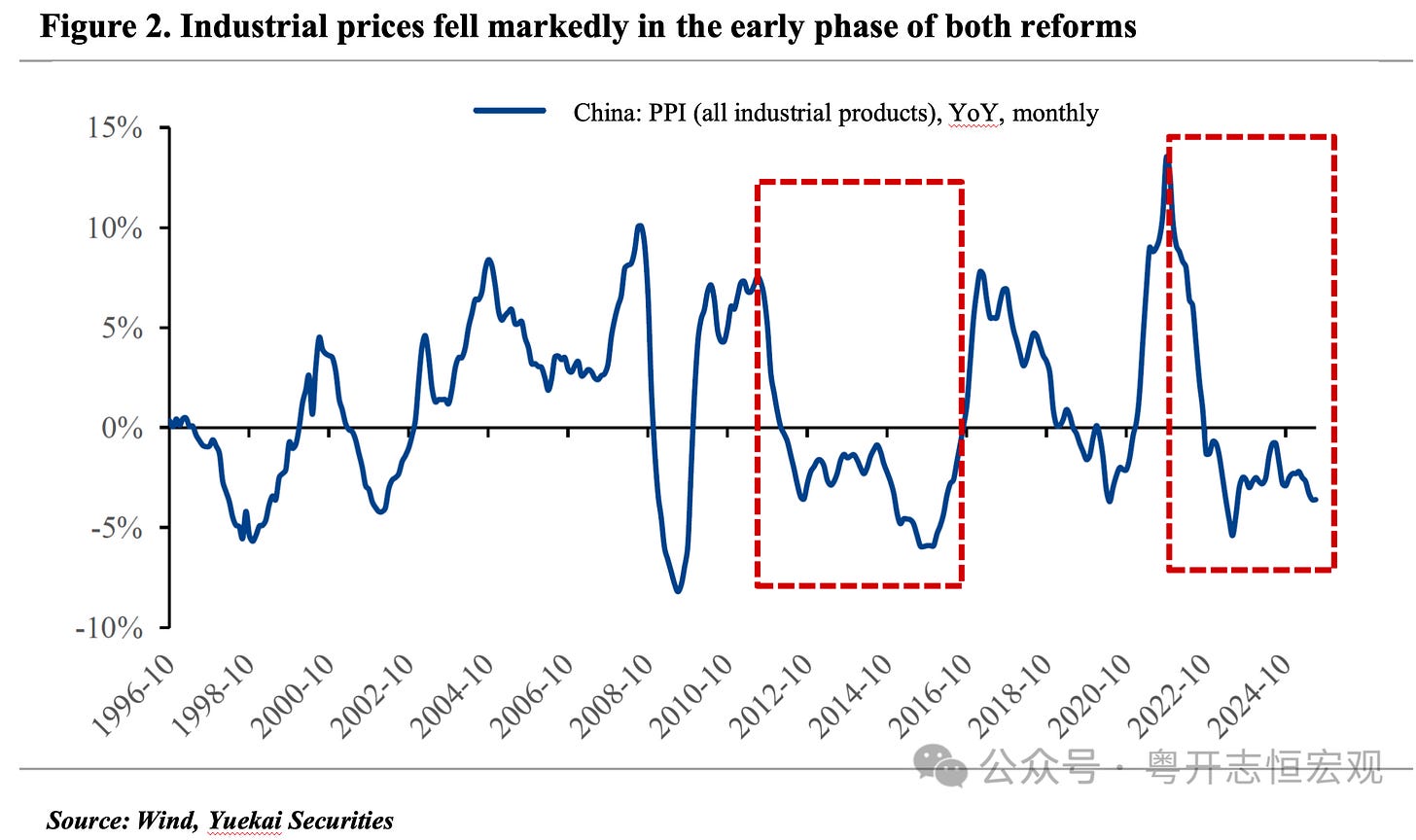

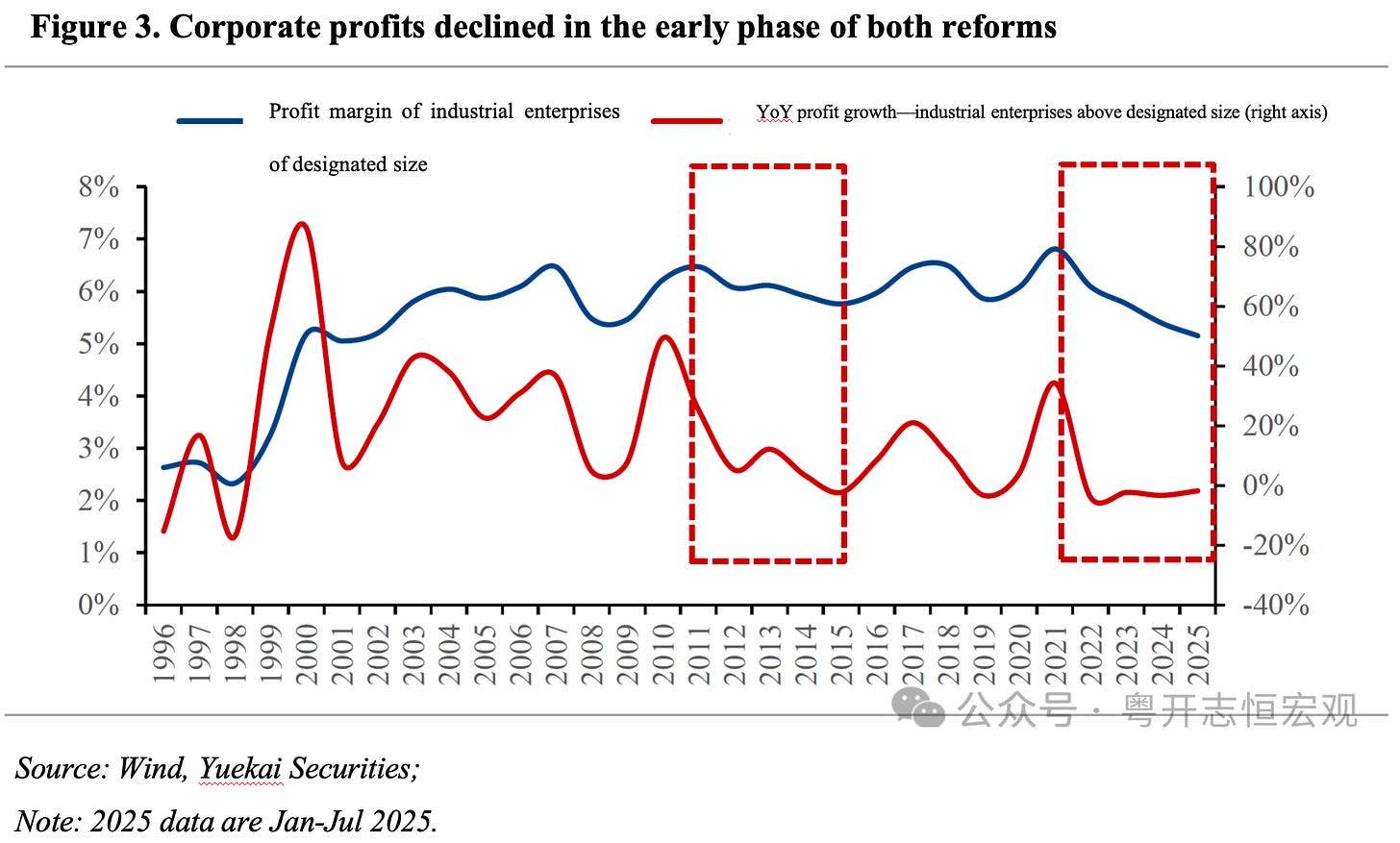

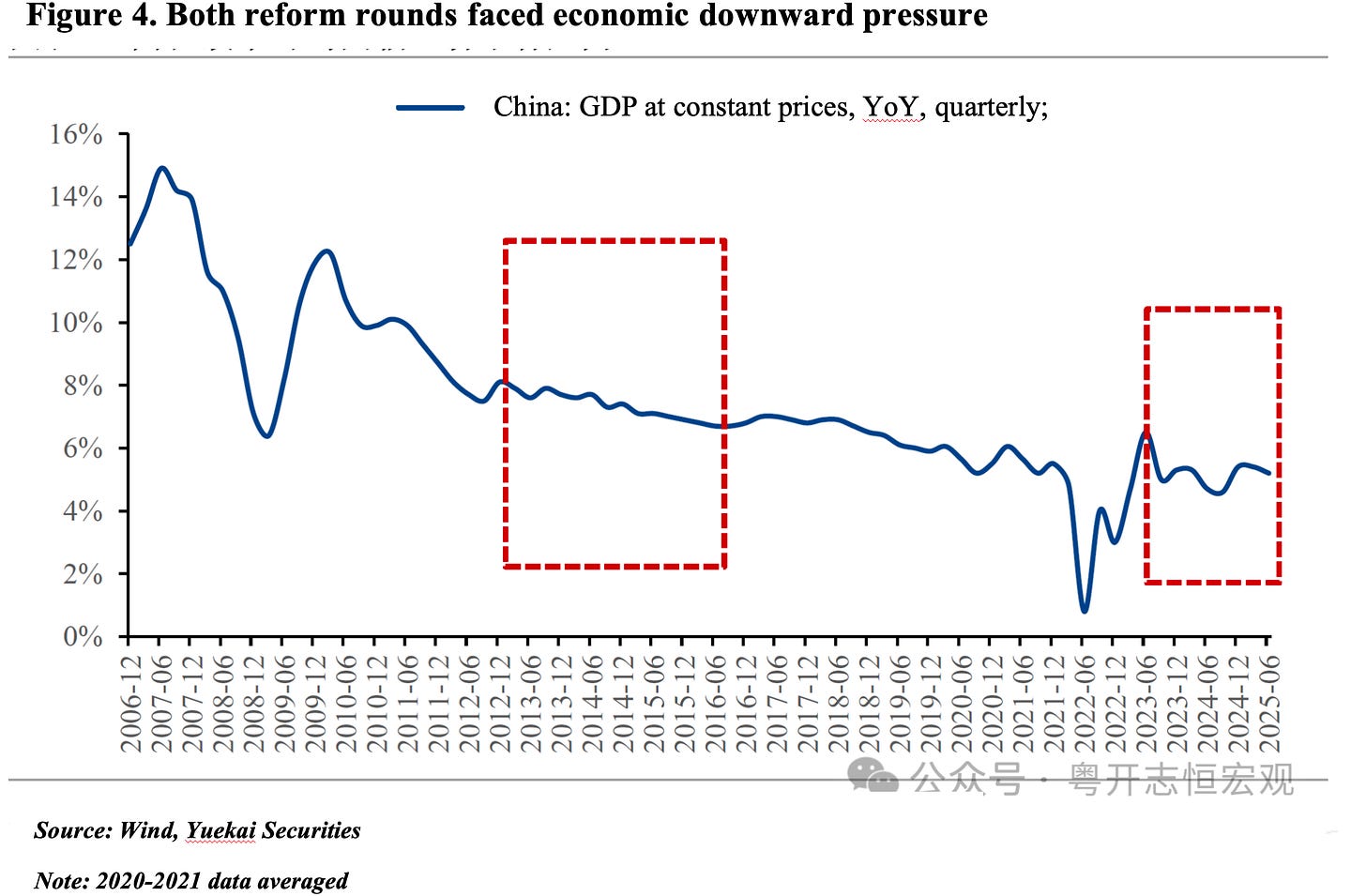

The report identifies four common phenomena between the two reforms: 1) a significant decline in industrial capacity utilization, 2) a sharp drop in industrial product prices, 3) a decrease in corporate profits, and 4) increased economic downward pressure.

Yet, there are also four key differences: 1) divergent macroeconomic environments and contextual backgrounds, 2) different industry sectors and nature of issues involved, 3) varying causes, and 4) distinct paths of implementation.

The full report is publicly available on Dr. Luo's WeChat account, and has also been published on Caixin (behind a paywall). I've translated the abstract of the report and some related charts and figures. Please note that Dr. Luo has not reviewed the English translation.

反内卷与供给侧改革有何不同?

Anti-Involution vs. Supply-Side Structural Reform: What's Different?

Abstract

Some argue that China's current push of "anti-involution" is simply a new round of supply-side structural reform, even calling it "Supply-Side Reform 2.0." The core tension behind anti-involution is a structural mismatch between supply and demand, which has led to falling capacity utilization, price declines, shrinking corporate profits, and intensifying downward pressure on the economy — phenomena that do resemble the backdrop of the previous supply-side reform drive in 2016. So in what ways does the present anti-involution agenda differ from that reform? Is it a replay, or does it feature new trends? Building on our earlier report, The Causes and Governance Pathways of Involutionary Competition, this piece focuses on these questions.

I. Similarities between anti-involution and supply-side structural reform

Both are responses to a structural supply–demand imbalance. Their common manifestations include:

1) a pronounced decline in industrial capacity utilization;

2) a sharp drop in industrial product prices;

3) falling corporate profits; and

4) heightened macroeconomic downside pressure.

II. Anti-involution is not a simple repeat of supply-side reform: four key differences

Different macro settings and historical context. Both phases face insufficient demand, but demand proved more resilient during the supply-side reform years. Todays anti-involution phase confronts more acute demand shortfalls amid a shrinking population and a structural reversal in real estate supply–demand, with both property and exports weakening at the same time. During supply-side reform, property entered an up-cycle after destocking, and a global upswing buoyed exports. In the current phase, property is in a deep, protracted down-cycle, and tariff wars are increasingly weighing on exports, making demand weakness more pronounced.

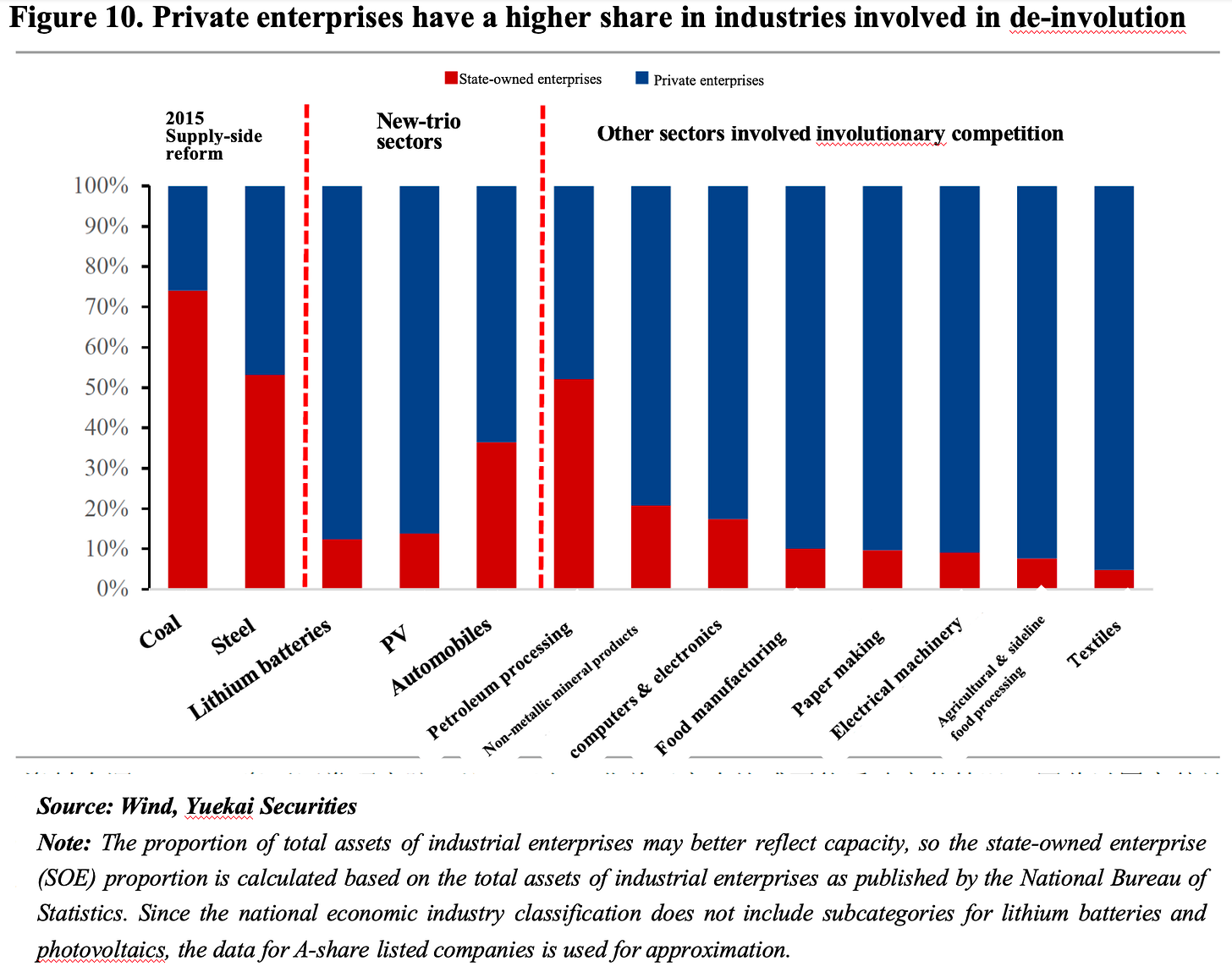

Different sectoral scope and firm composition. Supply-side reform concentrated on upstream and traditional industries, such as steel, coal, cement, which are dominated by state-owned enterprises. Anti-involution covers a much broader swath: upstream, midstream, and downstream, and has spread into the "new trio" industries (NEVs, solar PV, and lithium-ion batteries) and the platform economy, with the corporate base dominated by private firms.

Different causes. The previous imbalance largely stemmed from overcapacity that followed the tapering of stimulus such as the 4-trillion-yuan package back in 2008. Today's overcapacity is broader and reaches into emerging sectors, driven by multiple macro and industry forces.

The property chain's overcapacity reflects a structural reversal and deep adjustment in real estate, dragging on upstream and downstream staples such as building materials, home appliances, and furniture.

Export-linked overcapacity, primarily concentrated in labor-intensive segments, owes to global slowdown and tariff frictions.

Overcapacity in emerging industries is tied to sectoral technology dynamics and stage of development: before a dominant technology emerges, firms place parallel bets; once a standard takes hold, non-dominant routes are culled, stranding capacity. At the same time, many emerging industries are transitioning from expansion to stabilization with low concentration; numerous SMEs expand capacity and cut prices to avoid elimination, fueling "involution."

Fourth, platform-algorithm mechanisms coerce merchants into participating in campaigns that ignite online price wars, spill over into offline markets, and intensify vicious competition. At the same time, platforms leverage their dominant market positions to exert vertical pressure along the supply chain and shift costs upstream and downstream—compelling price cuts and longer payment terms—thereby institutionalizing "involution." It is therefore necessary to restore a fair competitive order and prevent platforms from coercing merchants into price reductions and other practices that degrade the industry ecosystem.

Because the underlying drivers differ, during demand downturns in the supply-side reform period, corporate investment fell as profitability deteriorated and capacity was cut; by contrast, "anti-involution" dynamics arise mainly in emerging sectors, where halting investment can permanently forfeit technological advantages and market share. Consequently, even while operating at short-term losses, firms feel compelled to keep investing to preserve their future viability, thereby creating a distinctive "the more you lose, the more you invest" dilemma.

Different implementation paths. Both phases require clearing excess capacity, bolstering demand, facilitating consolidation and market exits, coordinating fiscal and financial policies, and cushioning re-employment. Yet their levers, methods, and long-run pathways differ.

On policy levers: supply-side structural reform centered on the five priority tasks of cutting overcapacity, reducing excess inventory, deleveraging, lowering costs, and strengthening areas of weakness, focusing on efficiency upgrades in traditional industries. The anti-involution phase, by contrast, prioritizes institutional optimization, such as building a unified national market, while placing greater emphasis on science-and-technology innovation and the cultivation of "new-quality productive forces."

On methods of execution: supply-side reform made calibrated use of administrative tools to achieve capacity-cut targets. In the anti-involution phase, where private enterprises account for a larger share, greater reliance is needed on rule-of-law and market-based instruments: (i) tighter supervision and legal enforcement to regulate market competition; (ii) upgrading technical standards and raising entry thresholds to improve market entry-exit mechanisms; and (iii) a stronger role for industry associations' self-regulation.

On long-term trajectory: supply-side reform centered on short-term supply–demand rebalancing. The depth and breadth of involutionary competition, however, far exceed that period. Beyond guiding a near-term rebalance, durable governance mechanisms are required:

(i) in addition to counter-cyclical measures to expand domestic demand, proactively advance coordinated "state assets–fiscal–social security" reforms, increasing state-asset remittances to the budget and earmarking them to build out the social security system; (ii) refine local government performance evaluation systems and reform industry self-regulation; and (iii) adopt sector-specific, technology-aligned supply-side guidance while substantially increasing support for enterprise innovation.